The Via Consolare Project in Pompeii

|

||||||||

|

The Via Consolare Project in Pompeii

| ||||||||

| Home | Research | Internships | Team | Links | Contact | |||

| Summary | 2005/2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | VCP 3D |

| 2019 |

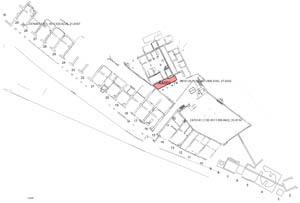

Figure 1. Plan of the location of AA005 within the area of the Villa delle Colonne a mosaico.

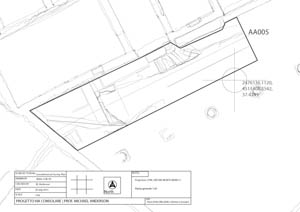

Figure 2. Detail of area AA005.

Figure 3. Satellite photometric of Insula VII 6 with 2014 research areas indicated.

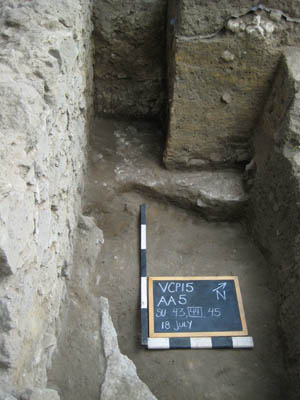

Figure 4. View of AA005. |

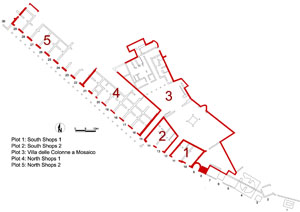

Field Season 2015 During the summer of 2015 with the kind permission of the Ministero dei Beni e delle Attivitŕ Culturali d del Turismo e la Soprintendenza Soprintendenza Speciale per i Beni Archeologici di Napoli e Pompei and with great assistance from Prof. Osanna, Dott.ssa Stefani, Dott.ssa Capurso, Dott.ssa Pardi, and Assistente Sabini, members of the Via Consolare Project conducted archaeological investigations in the area of the Villa delle Colonne a mosaico as a part of our on-going research into the chronology, urban development, and utilization of the properties along the Via Consolare, from Pompeii’s surburbium to its forum. Research was undertaken this year via the reopening and completion of a trench begun in 2009 but not yet completed (AA005) (Figs. 1 and 2). This trench was located within the raised bank upon which the Villa sits, between the core structures of the villa proper and a row of six columns on its south-western side. The main goals of this season’s archaeological research were the following: 1. Investigation into the sub-surface of the core of the Villa delle Colonne a mosaico, in order to recover the virtually unknown earlier history and chronology of the development of Villa, its shops and dependencies. Particularly important was the hoped recovery of sufficient ceramic evidence to permit the various phases of the development to be dated with precision. 2. Coordination of wall stratigraphic unit information and wall analysis initiated in 2009 into a broader understanding of the relative sequence of development of these properties, including the checking of data collected in 2009 in preparation for GIS database entry. 3. Complete 3D recording of the Villa and its dependencies, and all excavated deposits using Total Station Survey and open-source Structure from Motion (SfM) technologies to provide a complete, volumetric 3D record of standing remains and our excavation. 4. Recording, processing, and analysis of small finds and ecofacts recovered from the current trenches in concert with excavation in order to provide immediate chronological feedback and to speed the process of publication. 5. Identification of areas of the Villa and its dependencies requiring further examination and the localization of necessary areas for future sub-surface investigation. The great majority of these goals were achieved successfully during the summer of 2015. The completion of the excavation of AA005 produced a wealth of new information about the history of the villa and the early topography of the area, indicating that the current visible topography is actually the result of several significant phases of land-raising or terracing, generally employing re-deposited elements of natural soils that must have come from elsewhere. Sufficient datable ceramic and numismatic materials were recovered that we may be sanguine about the future provision of solid dates for many of these changes after the analysis of this material. Analysis and reanalysis of the standing remains permitted the coordination of checking of data recovered in 2009, and the refining of our interpretations. The extension of the work we had already completed in the shops outside of the Villa to include an analysis of the central core of the Villa, its sacellum, viridarium, and triangular tomb access space, has permitted much of the relative sequence of the whole villa complex to be identified and documented. This material is now ready for entry into our GIS database during the off-season. In addition, barring a few small additions, the Villa and its dependencies have now been entirely surveyed, and scanning via SfM (structure from motion) technologies is complete, permitting the creation of a complete 3D model of the Villa and its dependencies during the off-season. The end result will integrate neatly with current efforts to produce a new plan of the city currently being undertaken by the SAP. In 2015 this work continued with the complete recording in centimetric three-dimensional detail of all aspects of our excavation and research, including each stratigraphic unit, feature, wall, and surface. Many of these have been processed in-field producing point clouds of hundreds of millions of geo-referenced points. Once meshed, these will be coordinated into a complete, spatially-referenced, three-dimensional model of the excavation, including all sub-surface deposits, features, and surfaces at an unprecedented level of detail. This work is combined with 3D topographic survey of each trench which serves to interconnect all 3D scanning from Structure from Motion with traditionally hand-drawn plans into a complete, geo-referenced record. |

|

Archaeological Area AA005 in 2015

The 2015 season included the excavation and extension of a trench begun in 2009, against the southern wall of the core of the Villa delle Colonne a mosaico (Fig. 7). Already in 2009 the edges of a modern intervention running through the centre of the colonnade had been identified. Though seemingly not published, this earlier sondage was likely a part of the later investigations of Maiuri. Fortunately this earlier trench did not run against either the walls or colonnade of the Villa, instead leaving a baulk of a largely consistent distance from them, and therefore also leaving undisturbed the ancient stratigraphy in these areas. The excavations by the VCP in AA005 in 2009 had commenced late in the season, so there had been adequate time to establish the modernity of the central cut and the likely antiquity of the surrounding remaining deposits but insufficient time to complete our investigations. Therefore the area was subsequently sealed with a tarp and backfilled to be returned to at a later date (cf. the report for 2009). The VCP’s focus of study returned to excavation of the Villa this year, reopening the same area and extending it to encompass two thirds the length of the colonnade. Due to the fragility of the columns of the colonnade, a buffer of one meter was left from their bases to ensure that their stability would not be compromised and a small supporting baulk was left against the south Villa wall, particularly where a large fissure was visible. The resulting trench excavated this year was a 2.5 by 10.5 meter long strip, running from west wall of the colonnade to just beyond the eastern threshold steps of the Villa. Working from the knowledge gained in 2009, little time was wasted in identifying the continuation of the modern trench excavation to the east, and this area was then used to great effect in providing stepped access to the trench. Excavation of the ancient stratigraphy around the margins of this trench yielded a great deal of information about the Villa and the evolution of its colonnade, presenting six phases of use through its existence and providing subsurface correlation for our interpretation of the standing masonry. Phase 1 – "Black sand" and levelling deposit The earliest activity detected in our excavation was the deposition of a large levelling layer of soil over top of grey/black volcanic sand that appears similar to that found in other areas of the VCP’s excavations, as well as the work of many other projects of excavation across the city. The black sand has been interpreted to be a component of the natural sequence of soils, often devoid of human activities and likely associated with a period of volcanic activity period either prior to inhabitation in the area or long after any earlier evidence from the Bronze Age. Deposition of an initial levelling layer may have been carried out in preparation for the first constructions associated with the Villa, or perhaps were an attempt to even out or alter the original topography of the area after its construction. Phase 2 – Villa construction Phase two saw the construction of the Villa’s primary build in three bands of construction material (cf. the architectural analysis below for full discussion of construction in this phase). The core of the Villa structure was characterized by Sarno quoining at the portals (doors, windows) and very deep foundations, indeed so deep that neither the bottom of the wall nor the construction trench cut and fill for this wall were reached on its south face during the 2015 investigations. The southern perimeter wall of the Villa (wall 5) made up the northern boundary of the VCP’s excavations, but due to the depth of material at the west extent of the trench and the standing baulk supporting the majority of the wall, only a small, approximately 30 cm wide portion of the wall face was excavated to depth. It may be presumed that the wall was cut into the deposition layers of phase one, but further excavation will be necessary to demonstrate this connection. A mortared earthen surface (SU 43/47), sloping down from east to west, came up to the south face of the Villa perimeter wall and formed the first deliberately-constructed surface intended for activity in the area of the later colonnade. The slope of the surface mirrored the slope of the fill levels below, and while it seemingly was deposited to make the area more appropriate for the placement of the surface, it notably did not achieve an even level. The gradual E-W decline seems to be a deliberate feature, perhaps for drainage of the front area of the Villa toward the area of the Via Sepolcri at the presumed bottom of the grade. The extent of this surface, and indeed whether there was a more substantial final floor surface on top of this surface, is unknown, but it was visible in the full N section in our excavations, and in much of the S section as well (Figure 5). Phase 3 – Retaining wall, drain, and a level raise After some time, changes to the external south face of the Villa were made, raising the level of the space and presenting a more monumental frontage. This work began with the construction of a substantial north/south wall in black lava with a fine, professional, resilient grey mortar (SU 6). The character of this construction, using large, roughly hewn, irregular blocks of lava and with unfaced, seemingly hastily applied mortar, suggested initially that its construction may have been modern, and it was interpreted as a baulk left to the west of modern excavation trench that ran through the middle of the colonnade (Figure 6). However, with further excavation the antiquity of the wall’s construction became undeniable, and its unusual qualities must be explained by its intended function. Most telling was the discovery of five scored marks the mortar of the south face of Villa (wall 5) made to guide the placement of the new wall and where it was meant to abut wall 5. One vertical scored guideline on each side of the wall’s construction dictated the point at which the foundation cut for the builder’s trench should be made, and two additional guidelines, inset by approximately 10 cm from the first two, showed the vertical line of the wall’s construction itself. In support of this unprecedented indication of the process of ancient building construction method, the foundation trench on the east side of the wall lines up perfectly with the outer scored guideline, while the construction of the wall itself falls right at the inset guidelines (Figure 7). Excavation on the west side of the wall did not reach a sufficient depth to access the adherence to the construction guide lines on this side. Gauging from the close respect paid to these marks on the east however, it is likely they were also respected on the west. The fifth scoring mark, perpendicular to the first four, demonstrated the approximate height of the wall’s final construction, which was clearly never intended to be a full height wall for delineating a room, but instead a retaining wall for the raising of the surface level to its east. The space west of the wall (SU 6) seems to maintained the level of the previous phase, perhaps raised slightly above the level of phase two’s surface, but not substantially. That the wall (SU 6) was built for the purpose of retaining material to the east gives reason for its unusual building qualities, since the wall was never intended to stand above ground level on that side. In fact, it seems as though the eastern side of the wall was being filled in even as it was being built, as is shown by splatters of mortar fallen from the construction of the wall that mixed in throughout the levels of soil deposition (SUs 42, 46). The area to the east of wall (SU 6) indeed was raised with the deposition of a large volume of soil that was all but devoid of artefactual material (SU 48), nearly up to the level of the top of the wall. It is presumed that the stylobate wall below the columns (SU 11) recovered in 2009, running the length of this area was also constructed during this time, doing the double duty of supporting the construction of the columns atop it and forming the southern retaining wall for the soil deposited to the east of wall (SU 6). Perhaps the construction of the columns was the reason for the raising of the level of this area, creating a raised porch-like area for the colonnade. A drain (SU 27) was also constructed at this time, built in a black lava and fine, grey mortar, immediately atop the exposed surface (SU 47). The gradient of the drain ran northwest to southeast, exiting the door of the Villa at its eastern side. The source of need for the placement of this drain is as yet unknown. The same soil (SU 48) that raised the level of the entire space and filled in the level to the east of wall (SU 6) also ran over the construction of the drain. Additionally, a Sarno block (SU 30), present at the doorway to the Villa, may have been installed as the threshold stone for this phase of the Villa, as it is abutted by the same deposition of soil (Figure 8). No final surface survives from this phase, but a river pebble floor surface may have served as the finished floor at this time. Considerable elements of this floor were found deposited in later phases, apparently after it had been broken up and removed. Phase 4 – Shops and defining space Activity in phase four brings the levels on either side of wall SU 6 to the same elevation through the deposition of two layers of material on the western side (SUs 55, 56, 58). To retain these depositions, the westernmost wall of the Villa court was constructed (wall 4), also delineating the eastern boundary of the shops along the Via dei Sepolcri, but leaving two doorways open to allow access into the vaulted rooms created behind these shops. The construction of this wall and filling of the space to its east, similar to the construction of wall SU 6, preserves some of the process of construction, in that mortar splatter at the base of the wall’s construction remains preserved by having been buried immediately by soil deposition (Figure 9). Much of the construction of this wall is carried out using broken fragments of river pebble floor, suggesting that, as mentioned above, a floor of river pebbles may have been put out of use and destroyed and then its fragments incorporated into other building constructions in the area. The soil deposited to fill up the space between the west wall (wall 4) and wall SU 6 was rife with a particularly characteristic selection of materials, especially agricultural remains with a high volume of carbonized olive pits, charcoal in general, a wide range of pottery forms and fabrics, and iron. The material suggests that the source of this deposit was fairly affluent, with participation in agricultural production, indeed perhaps from the Villa itself or its environs. Phase 5 – Pipe, levelling up, surfaces, and another drain. Phase five saw a number of significant changes in the Villa, as demonstrated by changes to the area of the colonnade. Most notably among these changes was the installation of a lead water pipe. The pipe was brought in through the northern doorway of the west wall (wall 4) and ran nearly due west, crossing the western space of the colonnade from corner to corner. The trajectory of the pipe suggests that it may have provided water to the street fountain between the two sets of shops along the east side of the Via dei Sepolcri. For its installation, a shallow, linear trench (SU 54) was cut through the latest deposit of levelling fills on the west side of wall SU 6, even cutting straight through the wall itself (Figure 10). The pipe was laid into this cut, which was then filled and the room levelled up with the same deposit as that filling the cut (SU 39). To this was then added another large deposition of soil, broken pottery, and other debris (SU 34). Meanwhile, on the east side of wall SU 6, other changes were being carried out. The earlier drain (SU 27) was put out of use by two actions. The first was the cutting of a large pit to its west (SU 52), undermining part of the drain. This pit was filled with large, bulky rubble, and notably fragments of river pebble flooring that were dumped in face-down and occasionally stacked, and a large volume of mortar, materials pointing to a more general redecoration of the Villa at the time (SU 49). The second action that put the earlier drain out of use occurred to its west, where a new drain was constructed (SU 50). A cut was made into the levelling material deposited around the earlier drain and the new drain was installed on a different alignment, utilizing the earlier drain’s outflow point at the Villa’s threshold. The new drain construction, carried out in a soft, yellow-brown mortar with large white lime inclusions virtually identical that which characterizes many of the constructions of the fifth phase of the Villa’s evolution, was fairly ad hoc, utilizing irregular tile fragments to build up the walls of the channel and large sherds of a dolium for its cap. The build of this drain overlapped one of the channel walls of the earlier drain, suggesting that the previous drain had been exposed and its cap removed during the construction of the new drain (Figure 11). The purpose of the drain seems to have been solely the evacuation of water, while the build-up of sinter at the base of the channel and a very fine, entirely sterile silt deposit above that suggest that it was in regular use for some time. It is likely that this drain served the water feature constructed in the southeast corner of the Villa’s central court during this phase. The lead pipe, the new drain, and the pit cut with its river pebble floor fragment fill, were then covered over with a series of hard packed earthen surfaces (SUs 5, 22, 26, 32) that ran over the entire space of the colonnade, abutting the Sarno threshold stone and running over the wall SU 6. This surface was then covered, at least in its eastern part, by a whitewashing of white plaster (SU 28). The outer face of the Villa’s south wall was plastered at this time as well, perhaps indicating that the white plaster (SU 28) was simply extra material disposed of once the wall had been plastered. Any final surface associated with this phase of activity did not survive the changes of the subsequent phases. Phase 6 – Levelling up again, raising the drain, and black lava threshold stones The final ancient phase of development evident in the VCP’s excavation raised the level of the colonnade yet again. A rubble deposit (SUs 10, 25, 31) was spread over the whole area, likely serving as a subsurface levelling layer for a floor surface that, again, does not survive. It is possible that this surface, like earlier ones may have been of beaten earth. At the same time, new thresholds were installed in the portals through the south wall of the Villa’s core; at the western door, a single black lava block was inserted, while the eastern doorway received a series of smaller blocks that created two steps up to the ramp that divided the eastern and western sectors of the Villa and provided access to a second story. Commensurate with the raising of the colonnade elevation, the drain (SU 50) required alterations to extend its utility. A cut through the earlier surface provided access to the drain’s channel, and a vertical construction (SU 29) was made to join the earlier elevation with a channel under the new black lava threshold. This alteration was made with dolium fragments and Sarno stone, held together with a second version of a yellow-brown mortar (Figure 12) also found in some of the latest changes to the Villa's walls. Finally, a bench was constructed, its placement guided by scoring in the plaster on the face of the Villa’s south wall in the same way that the scored guidelines for wall SU 6 were made. The technique of planning the construction process had seemingly not changed. Phase 7 – No evident activity in AA005 AA005 did not experience changes during this phase, which is present in the construction history of the Villa walls. Phase 8 – Modern interventions At some point in the modern era, perhaps under the direction of Maiuri, a large, rectangular trench was cut through the centre of the colonnade court (SU 13), as mentioned previously (Figure 13). The fill of this cut consisted of churned soil nearly devoid of artefacts, but including a high volume of lapilli. It is possible that these lapilli derive from the cutting back of the scarp of unexcavated material to the east of the Villa, which also appears to have occurred at this time. |

Figure 5. Surface visible in section and exposed below the threshold stones.

Figure 6. Wall SU 6 construction.

Figure 7. Construction guidelines for wall SU 6 and foundation trench.

Figure 8. Sarno block with fill layers abutting its placement.

Figure 9. Mortar splatter at base of wall.

Figure 10. Installation of the lead pipe cutting the wall SU 6 and running through the (now sealed) doorway.

Figure 11. Drain construction on a new alignment from previous drain construction.

Figure 12. Drain vertical extension to match the new black lava threshold.

Figure 13. Modern excavation cut through the Colonnade court.

Figure 14. Plan of the Villa della Colonne a Mosaico with VCP assigned numbers.

Figure 15. Three-band construction technique of the original villa. |

Figure 16. Sarno limestone and tuff voussoirs.

Figure 17. Large rectangular windows in western wall.

Figure 18. Circular beam holes for balcony or mezzanine.

Figure 19. Three columns inside the villa.

Figure 20. Five columns in the villa court.

Figure 21. Filled doorway ending access to corridor.

Figure 22. Narrowed windows in the western wall.

Figure 23. Wall 4 and western terminus of villa court.

Figure 24. Sealed corridor into caldarium.

Figure 25. Window construction in doorway.

Figure 26. Buttress walls inside the villa.

Figure 27. Square beam holes cut into the northern villa wall.

Figure 28. Second level with diagonally striped plaster.

Figure 29. Characteristic yellow-brown mortar of Phases 5 and 6. |

Architectural Analysis and Phasing of the Villa delle Colonne a mosaico

The 2015 season focused intensively on wall analysis and the re-examination of architectural phasing of the Villa della Colonne a Mosaico in Plot 3 and its frontage shops along the Via del Sepolcri (Figure 14). Previous architectural study of these structures was undertaken in 2008 and 2009, when the shops in Plots 1, 2, 4, and 5 were the central focus and were nearly completed. Preliminary analysis of the villa itself was also undertaken in these years. This initial research produced several interesting observations concerning the relationship of the villa and the shops as well as challenges regarding the original phasing and analysis of the villa.1 The full investigation of the chronological phases of the villa and the resolution of these questions were the object of intensive study for the first half of the 2015 season. These observations were subsequently enhanced by excavation of AA005 at the south-western entrance to the villa. Several key phases have been identified and have been correlated with the phases of AA005. These are explained in the remainder of this report. Phase 1 Phase 1 was characterized by the absence of the original villa structure, but probably the presence of some early levels of activity (mainly levelling) atop natural soils at what becomes the villa’s southern entrance. Evidence of this phase is present in AA005 only, which spanned the southern thresholds and entrances of the villa. Phase 2 Phase 2 is represented by the construction of the earliest core of the villa. The construction technique is characteristic and consistent throughout the entire structure. Exterior perimeter walls were constructed with a 3-band build of stone materials in opus incertum. Black lava stones were used at the base of walls to significant depth. This band of black lava was topped with bands of Sarno stone and red cruma, respectively. Corners were quoined with large Sarno stone blocks (Figure 15). Interior walls that created room divisions followed a similar pattern. Here, walls were constructed in opus incertum with Sarno stone on the bottom and red cruma at the top. Sarno stone and tuff quadratum blocks were used as quoins, wall ends, and possibly freestanding pillars. The construction of both the exterior and interior walls used a distinctive and durable medium grey mortar that is identifiable by its colour and the concentration of crushed, small black volcanic stone and white limestone inclusions. Excavation in AA005 immediately outside the villa revealed a levelling deposit and an early surface in this phase (Phase 2), actions that were undertaken in preparation for construction of the villa. The structure is roughly square in shape and open in plan (Figures 1, 2, 3). Room divisions in the original layout were few. The western sector of the villa contained six rooms including the fauces.2 Large rectangular doorways that shared a common decorative characteristic throughout the early villa provided access to and through these rooms. Sarno stone and tuff voussoirs formed an arch above the lintel in each of these doorways (Figure 16). The western wall (wall 32) contained large, rectangular windows with flat sills, which provided ample light and further contributed to the open space of the structure (Figure 17). The northeastern corner of this sector descended into a series of barrel vaults that run east and west and are currently below and obscured by unexcavated material and modern overburden. These barrel vaults were constructed with black lava opus incertum walls with cruma opus incertum vaults and employ the same characteristic medium grey mortar associated with the primary build of the villa. A long corridor that runs north-south divided the western and eastern sectors of the villa. The eastern sector was built using the same characteristic black lava, Sarno stone, and cruma opus incertum technique; however, it was characterized by a more confined and compartmentalised internal spaces. Rooms 26, 27, and 28 were defined by a series of curving walls and narrow, vaulted corridor that connected Room 27 and 26. The curvilinear features of these rooms and the restricted space suggest that they should be identified as an early, rudimentary bath suite. Room 26 constituted the caldarium and was probably heated by a simple brazier. Fresco remnants showing a black background with red bands were discovered on walls 86 and 90. A similar red monochrome plaster is visible in the first phase of corridor wall 116. These remnants suggest that a program of black and red wall painting, possibly late 2nd or early 3rd style, was present during the first phase of the villa and the first phase of its bath suite. The significant height of the walls of this primary build suggests that several sections of the villa were constructed with a tall roof, while other rooms supported small, light additional stories. A series of circular beam holes in wall 137 were constructed with the build of the wall and align with a small door opening at a second level height in wall 142 (Figure 18). These circular beam holes are believed to have supported a small balcony or hanging mezzanine that was accessible from this doorway and a set of stairs in Room 9. The internal architecture of this phase, however, does not suggest that a second story could have been supported across the entire villa. Phase 3 – Addition of some Luxury? Phase 3 included the articulation and decoration of the interior and exterior of the villa through the construction of eight tile columns. Three columns were constructed inside the western sector of the villa and run east to west; five columns, also running east-west, were constructed outside the villa, south of the main entrance in its court (Figures 19 and 20). The construction of these columns corresponds to Phase 3 of AA005, where the westernmost surviving column was placed atop a supportive retaining wall (SU 6). Each column was constructed entirely of wedge-shaped tiles with one curvilinear edge. The columns all use a durable grey mortar with small black lava and limestone inclusions, similar to that used in the initial construction of the villa core. These columns were eventually coated with an application of red monochrome plaster, though this may have occurred at a later date. The construction of these columns established a slightly more defined space within the western sector of the villa. The reason for their construction may have been more decorative in nature than structural. Phase 3 also included the renovation of the eastern bath suite. This renovation added a raised cocciopesto floor in Room 26 probably in order to create a small hypocaust system. Two small flues were cut into walls 94 and 112 to convey the heat from below to warm the room. The floor of the corridor between Rooms 27 and 26 was also raised with a cocciopesto surface and the barrel vault of the corridor was lowered in order to conserve heat in the renovated caldarium. Phase 4 This phase marks an important shift in the structure and function of the villa as well as the creation and incorporation of the shops in Plots 4 and 5. Each action undertaken in this phase facilitated and supported the creation of at least one additional upper story in the villa. Most of the large doorways, particularly those embellished with Sarno stone and tuff voussoirs, throughout the western sector of the villa were filled. This included doors in walls 13, 20, 25, 47, 137, and 147. Two windows were also sealed in wall 137. The sealing of these doorways and windows filled voids and strengthened the integrity of these walls, probably in order to support new or modified upper levels. Additionally, the fill of the doorway in walls 137 and 147 cut off access to the central corridor of the villa and the bath suite to the east (Figure 21). These architectural fills mirror rubble deposits and levelling fills in AA005 that suggest major renovations outside of the villa with the same motivation: to stabilize and construct upper stories in the villa. The once large, rectangular windows along the western wall 32 were narrowed and angled internally to continue to bring light from the outside, as a view was no longer possible since the space they had once opened onto was about to be filled with a barrel vault (Figure 22). The renovation of these windows corresponds with the construction of wall 4 and Phase 4 of AA005. The construction of this wall created a western terminus for the exterior of the villa (Figure 23). It also formed the back wall of the upper barrel vault of the shops in Plots 4 and 5, which were constructed at this time. This back wall not only defined the shops and necessitated the window narrowing. It also created a small triangular space to the west of the villa perimeter. This room was incorporated into the villa by closing access into room 8, punching an arched door through wall 32 and building a covered stairway down into this triangular space. The eastern sector of the villa and its bath suite underwent a third round of renovation at this time. The shortened corridor connecting Rooms 26 and 27 was ultimately sealed, perhaps in an attempt to more efficiently contain heat within the caldarium (Figure 24). In response to this blocked doorway, an arched doorway was punched into wall 92/93/94/109/110/111. This action also permitted new access into Room 28 from Room 26. The combination of the Phase 3 construction of the tile columns in conjunction with the sealing of multiple doorway voids, rubble level fills in AA005, and the construction of the shops in Plots 4 and 5 in Phase 4 suggest the creation of at least one upper story in the villa during this phase. The filled doorways, windows, and blocked corridor as well as the reshaped windows are linked by the use of a light grey and durable mortar with crushed black volcanic stones and limestone, similar to that used in the original construction of the villa core. The combination of these architectural renovations inside the villa would have been substantial enough to support at least one additional level. The creation of the shops along the western frontage, moreover, would have necessitated at least one upper story to maintain the dominance of the villa in the area and to continue to provide a view of the sea. The precise characteristics of this upper story however, remain somewhat unclear, but the beam holes that were cut into walls 33, 40, and 47 may have occurred at this time. Its form may have mirrored the smaller, lighter mezzanine or balcony that existed in Phase 2, but on the northern side of the Villa core. Phase 5 The following phase witnessed changes that were intended to support the extension of the second floor across more of the villa as well as possibly the addition of a additional (2nd) story. The phase is characterized by the use of an easily identifiable yellow-brown mortar with white limestone inclusions as well as the occasional use of river pebble flooring fragments as building materials. The same phase (Phase 5) is also present in AA005, where the same distinctive mortar was used in the creation of a second drain (SU 50) and fragments of river pebble flooring appear in deposits. Two new walls were constructed, wall 41/46 running south from wall 40/47 and an east-west wall running from wall 32. Some spaces between walls and pillars or columns were filled and supportive buttresses were also constructed. A window was constructed between the Sarno stone quoin and column in wall 34/39 (Figure 25). This opus incertum construction continued in an L-shape return to the east, where it acted as a buttress running east from column 35. The action also narrowed the entrance to this room (Figure 26). A second small supporting wall or buttress was constructed at the southern entrance to Room 17, an action that also narrowed the entrance to the room. These new constructions were completed to support a significant second (or possible third) level. The square beam holes that were cut into walls 33/40/47 are large and evenly spaced and would have supported very sturdy beams for a heavy floor of a 2nd level (Figure 27). A ramp was constructed in the corridor space that previously divided the western and eastern sectors of the villa, leading up to the second floor. A door for this level and the rooms it created was cut into the northern terminus of wall 135/136/137 and the walls of this second level were covered with a diagonally striped plaster (Figure 28). A few additional changes mark the transformation of the villa’s interior into a more utilitarian space. A water basin and cistern were constructed against wall 142 and partially in the doorway of this wall. This doorway was subsequently filled just above the cistern in order to create more stability for the upper story and the wall above the cistern. The construction of this cistern corresponds with the roughly contemporaneous construction of drain SU 50 in AA005. This second drain may have been necessary to accommodate the additional outflow from the new water storage feature in the villa. Phase 6 Phase 6 marked the penultimate phase of construction within the villa. It also marked the dramatic expansion of the villa and the creation of a viridarium space to the south, the construction of four new shops in the north in Plots 1 and 2, and further changes within the original villa core. Construction throughout the entire villa complex was characterized by a yellow-brown mortar with white limestone inclusions, similar to the mortar used in Phase 5 (Figure 29). Phases 5 and 6, however, are easily distinguished by the type and technique of building materials used. In contrast to the use of a motley combination of stones and floor fragments in Phase 5, Phase 6 demonstrates a more cohesive use of materials and construction techniques. In the southern viridarium extension and the shops of Plots 1 and 2 with which it shares a wall, ground floor walls were constructed of Sarno stone (viridarium) or black lava (shops and western wall of viridarium) in opus incertum. These were topped with lighter red cruma in the second floor. Brick frontages and quoins were common features as were opus mixtum vittatum quoins of grey and yellow tuff blocks that alternated with two ceramic tiles (Figure 30). The construction of the viridarium approximately doubled the size of the villa as whole. This expansion and the new viridarium incorporated a seemingly pre-existing sacellum, which appears to have maintained its use despite the extension of the property (Figure 31). It also produced the four elaborately decorated mosaic columns, for which the property was named, an intricate mosaic nymphaeum featuring the back of a nude Venus or Nereid and shell encrustation motifs, and a long fauces decorated with Fourth Style painted plaster (Figure 32). The construction of four new shops in Plots 1 and 2 extends the villa’s commercial property to the south as well. The use of black lava thresholds in these shops mirrors the insertion of lava thresholds at the southern entrances to the villa that occurs in Phase 6 of AA005. The characteristic construction elements were also present inside the original villa core, though they were dramatically smaller in scale. Three opus mixtum vittatum piers of grey and yellow tuff blocks that alternate with two rows of tiles were constructed in the centre of the western sector (walls 35/36/37/38, 50/51/52, and 138/139/140/141) (Figure 33). These piers can only have been built to provide additional support for weight above, probably a 3rd floor, as suggested by the abutment of previous buttress walls and tile columns (Phases 3 and 5) and the construction of the southern and easternmost pier in Room 10. This room in the villa had remained a relatively open space. A fourth opus vittatum pier of Sarno stone and tuff also survives in this area (walls 42/43/44), but appears to have functioned more as a podium or niche (perhaps for a lararium) than as a support. Its construction cut the southern face of the villa interior’s middle column and abuts the small buttress walls from Phase 5. It has no physical relationship with the other piers, however, but for a similar alignment. These new opus vittatum mixtum piers appear to have been constructed to extend the upper story and floor of the central villa across the entire space as well as support an additional upper story and peristyle. New square beam holes were cut into wall 137, extending north from the small mezzanine or balcony that had existed since Phase 2 (Figure 34). This pre-existing upper story was transformed into a sturdier floor, an action that necessitated the raising of the threshold in the upper doorway of Room 9 and the reconfiguration of some of the early circular beam holes that may have been damaged in the process of the extension. The expansion of this second story connected with the second story floor that was constructed in the north during Phase 5. Additional opus vittatum mixtum quoins were also constructed in the eastern sector of the villa and display the same characteristic building technique and distinctive yellow brown mortar. Though many of these additions are heavily obscured by modern restorations, the locations of their construction as wall quoins and frames for doorways (at walls 80, 82/83/84, 87/88/89, 102/103113/114/115, 131, suggest that they too were intended to serve a supportive function for the addition of more weight above. The utilitarian character of the western sector was increased by the construction of a cooking surface against wall 13. A second cooking surface is present in the core of the villa, against the adjacent wall 14; however, this is believed to be a modern reconstruction mirroring the presence of the first cooking surface. A millstone in room 10 is also preserved today. Its authenticity is doubtful but possible. All evidence of ancient mortar or materials has been obscured by modern intervention. Phase 7 Phase 7 is represented by a few final enhancements to the expansion of the villa that occurred in the course of Phase 6. First, a set of stairs providing access across a long carriageway leading into the villa from the Via del Sepolcri were constructed (Figure 35). They are now largely modern in reconstruction; however, guidelines in ancient plaster provide ample evidence for the original existence. These stairs, walls 208/209/210/211, were constructed against a layer of pre-existing plaster on the dividing wall between the western viridarium and the northernmost shop in Plot 2. A second set of stairs (walls 162/163/164) was also constructed following the expansion of the villa. These stairs provided access to a room above the sacellum that was incorporated into the villa property in Phase 6. These represent the final changes to the property prior to its destruction by the eruption of Vesuvius. Phase 8 The final phase occurred in the modern period. Modern intervention includes repointing of walls and forms of architecture in order to prevent wall collapse. Some walls and features, such as the second cook surface in the western sector of the villa, are almost entirely rebuilt. |

Figure 30. Characteristic building technique of Phase 6. |

Figure 31. Pre-existing sacellum. |

|

Figure 32. Nymphaeum in viridarium. |

Figure 33. Opus vittatum mixtum piers constructed inside the villa for additional support. |

|

Figure 34. Square beam holes extending the second story of the internal villa. |

Figure 35. Stairs providing access over the carriageway of the villa. |

|

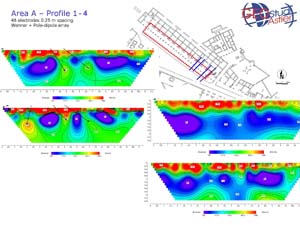

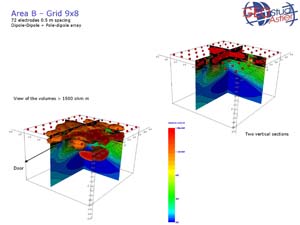

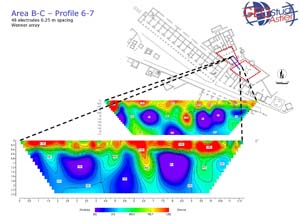

Geophysics in the Area of the Villa delle Colonne a Mosaico Undertaken in 2006 As a preliminary step in our research on the area of the Villa delle Colonne a mosaico, the VCP conducted geophysical research in several areas of the Villa with the assistance of Geostudi Astier s.r.l. Methods employed involved 2D and 3D Electrical Resistivity Tomography using an IRIS Syscal Pro of 72 nodes and 10 receiving channels analyzed in TomoLab and ERTLab, software developed by Geostudi Astier. Four profiles were taken between shops 17 and 19, running perpendicular to colonnade and extending through the shop and into the colonnade space. An area of the triangular space behind tombs 8 and 9 was also examined. A fifth section was placed on the southern side of the brick columns of the Villa facade, and two further transects were examined running through the doorway that separates the sacellum from the viridarium. Shop and Portico Transects The sections through the shops and colonnade were undertaken (Fig. 36) in order to examine the possibility of the shops in this area having once extended further to the west, as suggested by the analysis of the standing remains, which clearly show a blocked doorway in several of the facades. Further, it might be suggested by Maiuri’s hypothesis of an alteration in the direction of the Via Sepolchri. Two of the sections provided some support for such a thesis, with the northernmost two producing slight indications of vertical resistive features in the area of the colonnade in alignment with each other. These could potentially indicate an original shop front that had been cut back to the current arrangement for some reason. The northernmost section in this area (Profile 4) also showed signs of a resistive feature near to the current street kerbing. This feature is as yet unexplained. Grid Analysis Behind the Tombs Arranging the electrodes into a square permitted the analysis of a planar area of the triangular space behind tombs 6, 7, 8, and 9, (Fig. 37) resulting in two vertical sections and a 3D impression of the subsurface. Clearly delineated are the excavations of Maiuri, whose deep trench in this area recovered traces of “Samnite” graves.3 It is also clear that the areas not touched by these trenches have remained intact, particularly behind tomb 7 and would benefit from cleaning and possible excavation. The one vertical feature recovered could conceivably be another burial or possibly a component of the construction of Tomb 7. Section South of the Brick Colonnade (Profile 5) The single line of resistivity tomography undertaken near the core of the villa (Fig. 38) shows a clear distinction between resistive features and non resistive features on the eastern side, ending at roughly the depth of a metre and a half. This is probably the continuation of the raised platform upon which the columns were placed, and which was identified and clearly excavated in our trench (AA005) this year. Its termination aligns neatly with the end of the columns, suggesting that no further continuation would likely be found to the east. Profiles 6 and 7 – Modern Reconstruction of Ancient Tombs These were undertaken running through the sacellum and into the viridarium prior to having seen the publication of the tombs found in this area (Fig. 39). Excavation proved the linear features uncovered in the area (cf. Via Consolare Preliminary Report 2009) to be constructions in modern cement that surrounded the “Samnite” graves found in this area, and the voids clearly shown as areas of low resistivity, were the spaces of the graves themselves, filled with modern debris. Though it is unfortunate that the strongest correlation recovered from these geophysical examinations was a modern fabrication, that these were so clearly identified supports the conclusion that the remaining areas of interest or anomaly have meaning of value and are worthy of further investigation by sub-surface excavation. |

Figure 36. Transects carried out in 2006 in the shops.

Figure 37. Grid analysis behind the tombs.

Figure 38. Section south of colonnade.

Figure 39. Sections through the sacellum and viridarium. |

Figure 40. Decorated lamp fragments from AA005 recovered in 2015.

Figure 41. Resulting AutoCAD .dxf from 2015 survey showing extents of survey completed in 2009 and 2015.

Figure 42. SketchUp Reconstruction of the NE corner of Insula VII 6 from our studies of 2014.

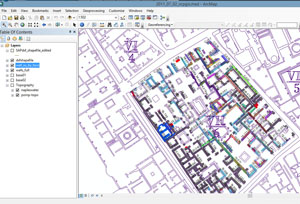

Figure 43. GIS walls analysis in Insula 7.6

Figure 44. 3D point cloud of the nymphaeum. |

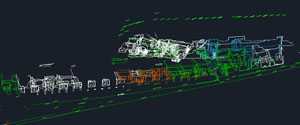

Finds Processing, Ecofacts and Pottery Analysis

Excavation in 2015 was paired with contemporaneous processing, analysis, recording, and study of all artefacts recovered from AA005. This season witnessed the complete cleaning, documentation, and preparation of all materials recovered from excavation. As a result of the absence of our ceramic specialist and lack of ability to access the finds from our previous seasons however, some material that would normally be discarded into the trench after analysis remains for study in 2016. Excavations recovered 88 kilograms of pottery during the 2015 field season, all of which has been washed, accessioned, and prepared for sorting, analysis, and illustration by Dott.ssa Keitel in 2016. Brick and tile recovered from AA001 and AA006-AA011 in Insula VII 6 was processed in 2014. During 2015, due to disruptions of the Grande Progetto Pompei, this material was recovered, cleaned, and stored, but will have to be studied in 2016. All soils from previous seasons have now been floated using a bucket-flotation method. As usual, light fractions have been reserved for study by environmental specialists and heavy fractions were sorted throughout the field season, recovering material smaller than the 0.4cm mesh employed in dry sieving. Finds included terrestrial and marine bones ranging from mouse to fish, shells, sea urchin and charcoal, including several seeds. 3D Topographic Survey of the Area of the Villa delle Colonne a mosaico This season, members of the Via Consolare Project continued the Total Station survey of the area of the Villa delle Colonne a mosaico which was initiated between 2006 and 2009. This season resulted in the near-completion of the wire-frame model of the greater villa and adjoining viridarium areas, which with the addition of the shops surveyed in our initial work, brings the model to nearly 100% completion. As in previous years, the 3D survey of the area was carried out with use of a Leica TCR805power Total Station, in combination with a Leica GMP111-0 Mini Prism. The resulting wire-frame model will be used to supplement traditional planning and 3D Structure from Motion (SfM) data capture in AA005 and of the extant walls, and to provide important insights into the actual plans, alignments, elevations, and other pertinent aspects of the standing remains in the area (Fig. 40). In addition, these data will provide a highly accurate (± 1cm) representation of the area, replacing previously available floor plans such as the Rica (1981), Kockel (1983), and Eschebach (1993) plans. The data captured this year will be added to that of previous archaeological seasons and are geo-referenced via connection to the geodetic points placed by the Soprintendenza Archeolgica di Pompei along the Via Consolare and Vicolo di Narcisso (020, 060, 061). An important role of the Total Station field survey is the recording of the archaeological excavations carried out in AA005. Each significant feature, elevation, and extent is meticulously recorded with this device, providing another efficient means of data capture, along with hand-drawn scale plans, 3D photogrammetry, and photography. Notable stratigraphic unit elevations within the area, the black lava retaining wall (SU6), and the drain features (SU27 and SU50) have all been accurately recorded and incorporated into the geo-referenced model of the greater villa area. The numerous benefits of this form of data capture are especially evident when used to supplement other forms of archaeological data recording and representation. Structure from Motion (SfM) software was first used by the VCP in 2010 to create a complete 3D image of excavation extents and standing archaeological remains. Although incredibly valuable for its detailed representation and accuracy, models produced by Structure-from-Motion are not inherently geo-referenced or scaled. However, the geo-referenced 3D wire-frame provides a framework to which SfM 3D images can be matched. When completed, the resulting data, integrating both the Total Station survey and SfM data sets, will be a complete and highly-accurate geo-referenced 3D model of the entire villa and associated areas. Further applications of the captured survey data include the use of the 3D wire-frame model to extrapolate potential architectural reconstructions of walls and features, further enhancing our understanding of the ancient built environment in the area of the Villa and its surroundings. The accuracy of the survey model created by the Via Consolare Project has permitted a more comprehensive interpretation of the various phases of the villa itself, and its relative chronology and changing relationship with the adjacent viridarium and surrounding shops. A visual assessment of the 3D model has already revealed interesting features of the villa and surrounding spaces, including the spatial relationships of the several floor levels encompassed within the villa, viridarium , and shops, and with the Via dei Sepolcri. Floor surfaces identified at the lower excavated levels of AA005 this year have provided tantalising clues to the original elevations of the earliest villa construction phase and its elevation relative to the street below. Indications of the original slope of the area upon which the earliest villa was constructed are provided within the 3D wire-frame model. When viewed in profile, the original elevations of the early villa construction as identified in AA005 can both be identified as matching the original elevation of barrel vaulted rooms on the northern side of the Villa core, as well as indicating a moderate slope that would have extended to roughly the elevation of the current Via dei Sepolcri. This reveals much about terracing in the villa and shops with respect to the original topography that is not apparent from plans or even from simple observation in situ. In addition, the 3D wire-frame model, the surveyed data will also be used to create a 3D reconstruction of the area with use of 3D visualisation software such as Sketchup and Blender3D. By importing the surveyed 3D wire-frame model into the systems, it is possible to extrapolate potential architectural features of the area, identifying further interrelationships, many which might escape notice through simple visual inspection. This process was used successfully in 2014 to design a potential reconstruction of the north-western shop of VII.6 (Fig. 41). Continued 3D reconstructions in this manner of the area of the Villa delle Colonne a mosaico will hopefully reveal many more interesting and exciting interpretations during the off season. Finally, the surveyed 3D model of the Villa delle Colonne a mosaico will be used to create a highly accurate GIS phase-plan of our research areas (see Fig. 42). Data captured through this season’s excavation and wall analysis will provide enough evidence to create a visual representation of each phase of the villa, from its earliest construction to its final layout. This plan, identifying each phase in sequence is a valuable research tool, and greatly assists in the overall interpretation of the villa and surrounding areas. 3D Data Collection Excavation in AA005 was carried out with complete recording in 3D at a centimetric level of accuracy. Each stratigraphic unit (US), feature, and surface was recorded using Structure from Motion (SfM) technologies4 to extract millions of 3D points and colour information from an unordered series of photographs. After processing, these are meshed with Meshlab, software designed specifically for cultural heritage projects by the University of Pisa, and developed with the support of 3D-CoForm Project. Following this stage, each mesh is coordinated into a 3D model including all surfaces of each deposit, wall, feature, and pavement. This permits a complete reconstruction of the entire excavation and even the virtual ‘re-excavation’ of deposits recorded in 3D. Mesh results are coordinated within the wire-frame survey produced via Total Station survey, which provides the appropriate scaling and geo-referencing data for the production of a complete 3D model. |

|

Conclusions and Current Interpretations Archaeological investigations in the Villa delle Colonne a mosaico and the completed excavation of AA005 have provided a wealth of new data about the Villa and its dependencies, their development and alteration over time, and the early topography of the area. Though previously little studied,5 it is clear that the area of the Villa delle Colonne a mosaico holds considerable information regarding the manner and chronology of urban development of Pompeii, the driving forces behind the formulation of the urban fabric of the city, and crucially, how these forces were similarly or differently expressed in the area immediately outside of the city itself. Our research of this year has allowed this area of the city to contribute to the Project’s express goals of examining the process, chronology, and driving forces of urban development along the length of the Via Consolare, from the city core to its surburbium. At this time, it is therefore reasonable to present some of the major observations and possible implications of our results as they stand at the end of the 2015 field season. The Urbanized Suburbium – A Late Phenomenon? In his article on the Villa delle Colonne a mosaico, V. Kockel suggested that a large part of the Villa complex is relatively late in date, perhaps as late as the final years of the city. While definitive support of this conclusion awaits the analysis of the large assemblage of pottery we have recovered this year, it seems likely that the most dramatic expansions and alterations to the villa layout did, indeed occur late in its history, likely after the Claudian period, and perhaps even during the final years of the city. Extensive reuse of a distinctive broken pebble-surfaced floor, combined with the large pit in our excavation found to be filled with this material combine to imply a large scale expansion and reconstruction, while the use of the same material in the construction of the tomb that produced a famous blue glass vessel of possibly Claudian date now in the museum at Naples (No. 8) would support a post Claudian date for this phase of expansion. Even later constructions appear to be connected with a tomb (No. 9) that is so late in the sequence that it never received an inscription for its owner. This component of the Villa expansion includes some of the most enigmatic features of the complex. While it seems possible that at least some of southernmost shops associated with the Villa may have pre-existed this final phase of activity, it is clear that this moment witnessed considerable expansion, including perhaps improvements to the now-missing luxurious aspects of the Villa which were supported by the shops and their upper stories. It seems therefore, that the area outside of the city had only recently acquired its distinctively urban and city-like flair in the final years before its destruction by Vesuvius (though this observation may change after the dating of our ceramic evidence). Perhaps this was the suburban expression of the same population pressure that might be documented by the addition of second stories throughout the city at this time. Certainly, the Casa del Chirurgo, not far from the Villa, witnessed considerable expansion of its upper storey space during the post-Claudian period of the city. It is probably important that both the Villa and its shops at this time contained upper stories, and the Villa itself, had spread to sit squarely on top of the shops, which supported it both physically as a series of barrel vaults and monetarily in the form of the income they produced. However, given that other parts of the city, such as Regiones 1 and 2 appear to have been sparsely inhabited during the final phase of the city, perhaps what is really observable in this pattern is a process of urban centralisation, and the crystallisation of the importance of the trade and routes of transport around the city core and towards Herculaneum and Naples. Certainly the Villa and its shops were situated relatively close to the Forum and the ‘urban core’ of the city that has been suggested by the results of our excavations in Insula VII 6. If so, then this process clearly had spread over time to encompass a larger area, even including areas that were officially outside of the city limits. A Window onto the Process of Ancient Domestic Construction A surprise discovery of this season was evidence of the process of construction and planning at the building level. The wall in question was apparently constructed in order to retain soil and support the addition of grand entry to the villa with six brick column on high plinths, possibly representing luxurious additions of the Augustan phase (contingent upon ceramic dating). Plaster on the southern wall of the original Villa core, against which this wall had been built, showed clear signs of scoring, both of a line for the planned wall itself, and for the proposed foundation trench, which was wider on one side than the other. The wall, which was relatively thick (46cm), and provided with heavily packed and dense foundations and underlying fills, was constructed in conjunction with fills that filled up behind the wall to roughly the level of another score mark on the plaster, that was located on the side of the wall that was not originally filled. It seems therefore, that the process of planning this wall, included not only the precise measurement of the wall, and its foundations, but also the provisions of marks indicating their intended locations and the approximate height of the fills it was about to retain. Clearly these marks were intended to guide the work of the workmen who actually completed its construction, and provide a window onto one way in which domestic architectural planning was undertaken and architectural plans were brought into fruition. One might easily imagine a foreman or architect marking out the site in preparation for the planned work so that it could be continued by less skilled workmen without continued supervision. A similar process was at work with the addition of a stairway to access a range of upper stories over the carriage entrance to the Villa, in which the locations of the intended steps were marked with scoring on the plaster. Original Topography and Surface Raising Activities The scale of terracing and raising of the soil recovered in our excavations in the area directly against the original core of the villa suggest several, often quite dramatic, changes to the overall elevation of the area throughout its history, and imply that the original topography of the area was considerably different to its final phase. Such a conclusion is strengthened by the observation that the "hill" upon which the Villa delle Colonne a mosaico appears to sit appears to be a largely man-make construction of barrel vaults. The great depth of the southern wall of the core of the Villa that bounded our excavations this year (AA005) implies that the original topography was characterised by a gently sloping surface gradually declining from east to west, probably arriving ultimately at the elevation of the current Via dei Sepolchri. The original core of Villa appears to have been cut into this surface, and then received a levelling of soil and a beaten earth surface that continued to follow this general underlying topography. This arrangement was altered first by a retaining wall and a raising of the soil on the east by almost a metre, probably intended to support a porch-like entrance of six brick columns, possibly with a new Sarno stone step into the Villa. This implies similar floor raising activities within the Villa, that will have to be investigated via excavation in future years. Eventually, with the creation of a western wall to the Villa and the western shops associated with it, this topography was totally interrupted, and ongoing filling activities continued to raise the elevation of the Villa. The final step in this process, involving a lava stone threshold, even required the modification of a drain running out of the Villa core through the western doorway, the interior raised component of which had to be joined to the pre-existing lower drain by an awkward fix in the doorway. All of this combines to suggest that the original, gently sloping topography of the area was almost a metre and a half deeper than the final elevation of the area. This situation is difficult to reconcile with our excavations of 2009, which recovered volcanic soils that were apparently the beginning of the natural sequence a much higher elevation. Could it be that this soils had somehow been truncated in the area of AA005 and the Villa core, or does this suggest a more dramatic slope from the south to the north that was reversed by the construction of the Villa and its subsequent modifications? Certainly though at first glance the Villa delle Colonne a mosaico and shops appear to have been cut back into the face of a pre-existing hill, with the most luxurious Villa rooms placed at the top of the hill to take advantage of the sea views it provided, this cannot be the case. Analysis of the underlying components of the Villa and its shops reveals no such underlying hill, and the significant floor raising activities suggest that the situation may originally have been precisely the opposite. Indeed, the considerable barrel vaulting in the area gives the entire zone the aspect of the widespread vaulting under the Temple of Venus against the old course of the Sarno river, and it is possible that the areas around the Villa delle Colonne a mosaico had a very similar character. Certainly, the three story vaulting of the shops could easily have been matched by continued vaults under the Villa that faced towards the east and lie in the unexcavated volcanic debris to this side of the area. It is clear therefore, that more work must be undertaken in order to establish the original topography of this part of the suburbium of Pompeii, and to begin to explain where the mixed and re-deposited natural soils which were employed for raising the elevation in this area may have originated. Such an understanding is of importance not only in the urban history of the site, but also plays a role in understanding key elements in Pompeii’s history such as the Sullan siege of the city in 89 BC. Overall, the results of the 2015 field season have served to strengthen, support, and build upon the conclusions of our previous research. Nevertheless, there remain important questions to answer, especially within the core of the original Villa, and in areas where modern build-up has been most extensive. These questions will form the basis of our future investigations and excavations. As always, we remain deeply indebted to the Soprintendenza Archeologica di Pompei, the Ministero per i Beni e le Attivitŕ Culturali, Soprintendente Prof. Osanna, Direttore dott.ssa Stefani, dott.ssa Capurso, dott.ssa Pardi, and Assistente Sabini and extend our warmest thanks for their kind and continued support and encouragement in our research activities. Our work could not have been done without their aid. Finally, we wish to thank our great friends at Bar Sgambati and Camping Zeus for their ongoing generosity and unending friendship toward the Via Consolare Project and its members since its inception. |

Figure 45. Closing image of AA005.

Figure 46. Closing image of AA005.

Figure 47. Closing image of AA005.

Figure 48. View down the Via dei Sepolchri towards the Villa.

Figure 49. View up the Via dei Sepolchri towards the Villa.

Figure 50. Work under way in AA005.

Figure 51. Work under way in AA005. |

3D point cloud of the AA005. |

|

|

||||||||

|

Website Content © Copyright Via Consolare Project 2018

| ||||||||