The Via Consolare Project in Pompeii

|

||||||||

|

The Via Consolare Project in Pompeii

| ||||||||

| Home | Research | Internships | Team | Links | Contact | |||

| Summary | 2005/2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | VCP 3D |

| 2019 |

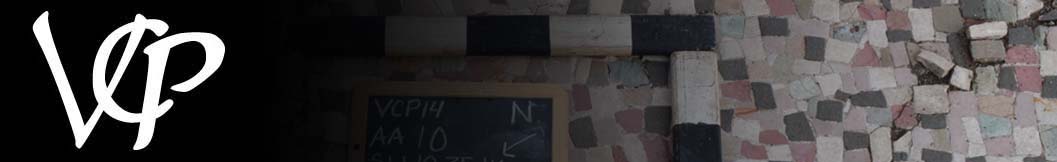

Figure 1. Plan of the locations of AA009, AA010, AA011 within Insula 7 6.

Figure 2. Excavation underway in AA010 in 2014.

Figure 3. Planning underway in AA009 in 2014.

Figure 4. Excavation taking place in AA011 in 2014.

Figure 5. Clearing the fauces of AA010 in 2014.

Figure 6. View of AA010 from the south.

Figure 7. View of Plot 8 doorway 14.

Figure 8. Potential early wall alignment visible at right and left extremes of photo.

Figure 9. Eastern wall of property with significant foundations – corner constructed in reused tuff blocks.

Figure 10. Characteristic brick band and quoin construction of the property. |

Field Season 2014 During the summer of 2014 with the kind permission of the Ministero dei Beni e delle Attività culturali d del Turismo, e la Soprintendenza Soprintendenza Speciale per i Beni Archeologici di Napoli e Pompei and with great assistance from Prof. Osanna, Dott.ssa Stefani, Dott. De Carolis, and Assistente Sabini, members of the Via Consolare Project conducted archaeological investigations in Insula VII 6 as a part of our on-going research into the chronology, urban development, and utilization of the properties along the Via Consolare, the area of the Villa delle Colonne a mosaico, and especially Insula VII 6. Research was undertaken this year via three trenches, all of which were located on the north-eastern corner of Insula VII 6 (Fig. 1). The first trench (AA009) encompassed the majority of the front room of the shop/cella vinaria1 situated at VII 6, 13-15 on the eastern side. The second (AA010), included the fauces and atrium of the property at VII 6, 10.11.16, running from the western to the eastern wall, and leaving only a small area unexcavated for trench access. The final trench (AA011), was a small sondage situated directly in front of doorway VII, 6 11 in order to investigate the point where the drain from within property VII 6, 10.11.16 exited onto the Via delle Terme. The main goals of this season’s archaeological research were the following: 1. Investigation into the sub-surface of the front room of the property at VII 6, 13-15 in order to recover any traces of an earlier construction history that might tie the area into the narrative already identified for the south-eastern corner of the block. This area was particularly important since the wall structure in this area, unlike anywhere else in the block, preserves virtually no traces of any earlier activity. 2. Cleaning and removal of modern debris from clearly visible preserved pavement within property VII 6, 10.11.16, in order to record the floor and to assess the possibility for further excavation in the area through very poorly preserved or missing areas of the surface. 3. Excavation of a small sondage in the pavement on the northern side of the block, to assess the presence or absence of modern disturbance and the degree of alteration that the northern kerbing stones might have undergone, and to document the drain exiting from property VII 6, 10.11.16. 4. Complete 3D recording of excavated deposits using Total Station Survey and open-source Structure from Motion (SfM) technologies to provide a complete, volumetric 3D record of the excavation undertaken. 5. Recording, processing, and analysis of small finds and ecofacts recovered from the current trenches in concert with excavation in order to provide immediate chronological feedback and to speed the process of publication. The great majority of these goals were achieved successfully during the summer of 2014. In AA009, excavations did not reach full depth or produce natural soils due to the recovery of a deep cellar under a collapsed AD 79 floor, meaning that excavation could not continue in this area this year. However, despite this, a considerable amount of information about the earlier phases of the area was recovered, because the building of the cellar had reused elements of a pre-existing construction in its lower elements. In addition, the material recovered from the upper layers of the eruptive material, combined with information on the wall structure that was uncovered in our excavations reveals much about the area, contributing greatly to our understanding of how that part of the block developed. In fact, it is now clear that the construction of the Great Cistern and its impact upon the southern and central areas of the block was even more significant than previously thought. It now seems likely that the north-eastern corner of the block was transformed into an early apartment block, of probably at least three stories in height, extending over the top of the Great Cistern and clearly built together as a large, concerted action that must have been on a civic scale. The process of creating this new feature of the urban environment involved some reuse of a previous structure, the walls of which remain on the northern side of the area under the current marble threshold and to the south under what was originally a broad opening with opus signinum floor. That the new building was intended to bear considerable loads is clear from the extremely broad foundations added on the eastern side of the area, and the reuse of large blocks of tufo di Nocera that probably belonged to the original structure. Each wall that was intended to bear the weight of the upper stories received a similar massive foundation, and all of the new walls contained a distinctive band of bricking in the middle of their opus incertumconstruction that appears intended strengthen the wall for yet further structures above. The third storey appears to have extended over the top of the Great Cistern, helping to explain the purpose of the rooms on the top level that have long been relatively enigmatic. From reed-impressed plaster found collapsed into the eruptive materials, it was clear that at least one room in the upper stories had lovely decorated ceilings of the 4th Style, suggesting a degree of refinement in decoration, even in a zone with quite a high level of occupation. It is also of note that if this interpretation is correct, then this would comprise virtually the only apartment complex similar to an Ostian "caseggiato" to have been identified within Pompeii, a city that is normally thought to have been buried at too early a date to have experienced aspects of the extreme intensification of urban housing clearly documented by the evidence in Ostia and Rome. The Casa a Graticcio in Herculaneum, sometimes heralded as an early example of the advent of multiple-occupancy dwelling in Campania, along with the apartment complex situated to the west of the Grand Palaestra at Herculaneum, may therefore have to cede primacy to this area of Pompeii, which appears to have undergone this change as early as the beginning of the reign of Tiberius.2 The cleaning of modern debris from the atrium of the small house or inn at VII 6, 10.11.16 provided additional information on this phase of transformation on the north-eastern corner of the Insula while also shedding some light on the earlier history of the area. In addition, this work uncovered a remarkable and well-preserved impluvium with marble mosaic decoration that must have been excavated by the publication of Spano in 1910, but which had never been photographed or recorded and as a result has previously received very little scholarly attention. The majority of the atrium area was cleared of modern debris, which in some areas had built up to roughly a metre in thickness. The opus signinum pavement of the fauces and atrium was found to have suffered greatly from damage from grass roots which, in growing in a lateral direction had run just under the surface of the flooring and fragmented it. In several areas however, the top surface of the floor was extremely well preserved, especially on the eastern side, which due to a thick layer of modern build-up, were too deeply buried to be affected by the root activity. Against the eastern wall, the curving arch of a small platform, which was possibly for cooking or heating, or may have served as a small shrine, was also freed from modern debris. In the centre, a beautiful impluvium was recovered that had been decorated with an unusual mosaic with large tesserae in four different stones. While the banding that had once encircled the impluvium had suffered considerable damage from plant roots, the base of this impluvium was nearly perfectly preserved, except for one large crack running through the centre that followed the line of a collapsed cistern recovered on the southern side of the impluvium basin. The closest parallels identified so far for the stone types and decorative design of this impluvium are the 1st Style floors of rooms surrounding the western atrium of the Casa del Fauno. This may therefore present an interesting chronological difficulty in the area. Certainly the small house, its walls, and the final phase floors cannot date before the creation of the Great Cistern, and therefore are of an early Imperial in date at the very earliest. It is possible that the impluvium was an element of earlier flooring that was reused and transformed into an impluvium basin. Certainly, the current arrangement of the basin does not appear to have been created for the current space, as it is unevenly aligned with the entrance fauces. Unfortunately, the generally high-level of preservation of the flooring throughout the room meant that this question cannot be completely resolved this year, but presents a tantalizing window onto the largely missing earlier phases of the north-eastern corner of the block. Subsequent changes to the area were also recovered in AA010. The opus signinum floor that went with the impluvium, was cut extensively for the creation of a new drain that ran down the fauces and emptied onto the street. However, rather than running simply from the impluvium, the cut also ran along the eastern side of the basin, continuing to the south until ending just under the small shrine or cooking platform. Within this cut, a drain, lined with a remarkably red waterproof plaster was found capped with reused roofing tiles that had been broken to fit in place. One of these tiles was stamped with the name ‘HOLCONIVS,’ which should be able to provide a solid TPQ for its creation. It seems clear that this action created an overflow drain for the impluvium’s cistern. However, it is much less clear how this cistern was drained prior to this moment. Possibly the drain originally ran to the east and had to be changed due to changes that lie outside the areas excavated this year. Once the course of the drain down the fauces had been established, a small sondage was opened into the pavement to the north of doorway VII 6, 10.11.16 (AA011). Here, it was found that on the northern side of the area a modern trench had been excavated for the placement of two different phases of water pipes. This was subsequently filled with a modern deposit of lapilli. To the south, much of the original lavapesta pavement survived. Between these two areas, sufficient ancient material remained to be able to trace several early activities, including a potential foundation deposit, and the re-deposition of a large amount of ‘natural’ soil mixed with plaster. It is likely that this area will need to be re-excavated in 2015 in order to finalise our study of these earlier levels. Above this, the drain that had been placed through the final phase floor of the atrium exited onto the street running towards the northwest. The actual point of connection for this drain and the street kerbing had been destroyed by the modern pipe trenches, which appear also to have disturbed a number of the kerbing stones towards the west, which are uneven and appear to have been repositioned. The fact that the drain had been broken meant that it was possible to excavate its contents, much of which appear to have originated from the moment of the eruption combined with continued drainage after the initial excavation of the area. Excavation of this fill produced a large number of interesting finds, some of which may assist in understanding the final phase layout of the house itself. Since 2010, the VCP has pioneered the use of open-source Structure from Motion (SfM) technologies for archaeological research at Pompeii. In 2014 this work continued with the complete recording in centimetric three-dimensional detail of all aspects of our excavation and research, including each stratigraphic unit, feature, wall, and pavement. Many of these have been processed in-field producing point clouds of hundreds of millions of geo-referenced points. Once meshed, these will be coordinated into a complete, spatially-referenced, three-dimensional model of the excavation, including all sub-surface deposits, features, and surfaces at an unprecedented level of detail. This work is combined with 3D topographic survey of each trench which serves to interconnect all 3D scanning from Structure from Motion with traditionally hand-drawn plans into a complete, geo-referenced record, that will be able to be integrated seamlessly with similar SfM work directed towards producing a map of the whole city. |

|

Archaeological Area AA009

The 2014 season included the excavation of a trench investigating the majority of the northeast corner shop in insula VII 6 (plot 8, doorway 14, so-called thermopolium of Epidius Sabinus) (Fig. 7). These investigations sought to uncover earlier phase shops, or whatever previous structures existed prior to extensive final phase construction. Before this year, the working theory for this area had been that an early phase of tuff frontage shops ran down the eastern side of the block, continuing those evident on the southeast corner, and that these shops were demolished for the construction of the 'Great Cistern' at the midpoint of the block. Excavation was intended to strengthen or refute this theory with the discovery of similar plot divisions, materials use, or other evidence. However, a rather different outcome resulted. Information from this area from earlier excavation is spotty. It is likely that the area was first uncovered by the Bourbons, probably in conjunction with excavations in the Casa di Pansa (VI 6, 1.8.12.13) that clearly were underway at this time as well. The western Vico delle Terme, including some of the northern side of Insula VII 6 appears to have been cleared in an image of Mazois in 1824, which also depicts the inital stages of work on the Casa di Pansa.3 This was supported in our excavations by the recovery an intact Bourbon pipe bowl found at the interface between modern and ancient layers. The first clearance of the back rooms of the shop probably did not take place until 1868.4 Both Fiorelli and Spano suggested that the shop was used as a taberna,, and Eshebach considered it a cella vinaria, likely based on the presence of dolia and serving counters at both doorways 14 and 15.5 Excavation in 2014 found no additional evidence to refute or support this interpretation, though what was recovered means that the potential for further information from this area is significant. The major outcome of this year’s investigations revealed a well-preserved basement level in the shop, as yet unexcavated from the primary eruption material. What this level may hold is sure to provide excellent evidence for the use and arrangement of a business at this very important location in close proximity to the Forum and Terme del Foro. Phase 1 – Early walls? The only potentially early phase evident in the remains of the area are two walls at the north and south boundaries of the room. Both were walls built primarily in sarno stone and cruma, and had a plaster facing on their inner surfaces, which were relatively similar in their composition (fine waterproof plaster with 40-45% inclusions of medium sand) (Fig. 8). The southern of these two walls is likely what Fiorelli was referring to when he spoke of early 'Samnite' foundations in "sarno stone" that underlay the construction of the shop, though it is difficult to explain why he would have identified tufo di Nocera as sarno stone. These walls, for their similar alignment, construction, and surface treatment, seem to be associated with each other. In addition, the fragmentary nature of the upper extent of the wall plaster suggests that these walls were not constructed and plastered for use in later phases of the shop, but were instead cut down or reused. It is suggested therefore that this early phase of the shop likely fronted east onto the vicolo delle Terme, perhaps taking advantage of a potentially wider street than is now evident and matching the other tuff frontages of the southern extent of the block. However, there is no further evidence that this proposed early shop had any construction in tuff, other than the ashlar blocks reused in the northeast corner of the later shop layout. Deeper understanding of these early walls and their association with any additional construction must await further excavation. Phase 2 – Multistorey shop The northeast corner underwent a significant change, possibly as a result of the construction of the Great Cistern and the reworking of the Forum Baths in the early 1st century AD. The walls from the earlier phase shop seem to have formed the basis of the north and south boundaries of a room in a new construction in this area. The eastern extent of the room was defined by a significantly thick foundation, replacing the probable frontage of the earlier shop (Fig. 9). As mentioned above, tuff quadratum blocks were repurposed to define the corner of the insula, clearly a secondary function of these blocks from the beam and plank holes that are evident in the inner faces of the blocks that are unrelated to their current position. Atop the early walls and these foundations were built walls with an easily-recognizable brick-stepped quoining with a band of brick at the level of a second storey (Fig. 10). This construction seems to suggest that the structure was intended to bear the loads of multiple storeys. The care with which these walls were created and their consistency in construction suggests a great deal of thought was put in to planning this construction to bear weight. The height of the great cistern and the significance of these walls implies that this property, and perhaps all the properties north of the great cistern, were built to at least a third storey. In addition to having great potential for vertical construction above ground level, AA009 also revealed that this property had had a basement level. Against the eastern wall foundation were found three steps descending to the north, supported on their west side by a wall constructed in in cruma and black lava rubblework (Cf. infra) (Fig. 11). These steps may have begun at a slightly higher point, perhaps incorporating a lava stone block in the corner of the property, but more likely this block formed the foundation for a brick quoin at the terminus of this wall that has not survived (Fig. 12). Regardless, the steps descended below a two-part vault. The first part of this vault was part of the general construction of the east wall, constructed in cruma and sarno stone, and showing evident shuttering on its underside for the creation of the vault (Fig. 13). This construction was augmented over the course of the stairs by a separate construction that is keyed into the thicker construction of the wall foundation of the east wall. The small amount of this construction that still remains in situ shows a distinctive build of a lighter grey mortar than the east wall and use of nearly 100% yellow tuff. The stairs would have descended under the yellow tuff vault to the corner of the property where the walls were plastered in a thick, course, white plaster and then presumably turned west into a room or rooms below the main floor of the shop. The basement walls were constructed in majority cruma with black lava stones, which also continued in an arch that would have comprised the vaulting of the downstairs room. The faces of this construction were plastered in a fine, finished white plaster that would also have covered the ceiling (Fig. 14). This plaster, as well as the plaster on the corner vault construction, were different to those plasters on the faces of the earlier walls, and the trajectory of the curve of the vaulted ceiling was such that use of the early walls as anything more than a foundation for the later walls is unlikely to have been the case. The ground floor of plot 8 doorway 14 had a opus signinum floor across its extent, extending south into the room served by doorway 15. This floor was at an elevation that matched the three-stone limestone threshold elevation (differing by only 2cm), as well as a wall scar that is traceable around the entire room, with the exception of the south wall. This floor, though now highly degraded, had blocks of fine marble set into it (Fig. 15). Phase 3 – Bar counters and an additional wall At some point later, minor changes to the space were brought into effect. A bar counter was constructed on the surface of the ground floor opus signinum to support three dolia. Three dolia-sized, circular spaces were left for cradling the vessels, two solely as construction supports, but the third most-northern space cut into the surface of the floor to accommodate a presumably larger dolium (Fig. 16). The counter was plastered and painted red. Likely at the same time, the brick quoin within the south wall was broken through to extend the south wall of the room to the west, built immediately over top of the opus signinum floor, very likely to have been the same opus signinum floor that covered the whole room and on which the bar counter was constructed (Fig. 17). Extending the wall may have been motivated by the construction of the bar counter at doorway 14 itself, and perhaps the construction of the bar counter at doorway 15. These two constructions are very similar, both having been finished with red wall plaster and having the purpose of holding dolia, suggesting that there may have been a need to define the spaces slightly differently to maximize their use. The construction of the wall over the opus signinum floor is one of the few indications that this wall was extended and not built to its full western extent in the first instance. It seems that the brick quoin at the end of its first construction was knocked down to allow the wall to adhere more successfully to a rough construction. Damage and modern consolidation makes observing the distinction between the two difficult, as well as deliberate construction of the extension in a style that matches that foundin the rest of the area, i.e brick-stepped quoining with a brick band. However, the quoin of the doorway at the end of the wall extension, while matching in general appearance, does not match in quoin execution. The width of the stepping does not match that of the quoin steps throughout the rest of the property, and it is at a different elevation. Phase 4 – Eruption In the last moments of Pompeii, the shop at doorway 14 was filled with lapilli and ash, as was the whole city. As the level of fill became extensive, the upper stories of the area appear to have begun to collapse. The opus signinum and bar surface of the shop ground floor however, simply disattached from the edges of the room, and sank relatively evenly about 50cm below the level of the threshold. What conditions might have caused this to occur are yet unclear, as the failure of the vaults below this floor would be expected to have created a much more uneven collapse. Some of the constructions of the vaulting certainly did crumble, exposing the wall and vault construction as discussed above (Fig. 18). Likely this was because large fragments of an equally thick opus signinum, likely deriving from second storey floors, fragmented, fell, and broke through the lower floor and underlying vaulting. This was clear in the excavation of eruption materials, from which were recovered large fragments of these upper floors. Phase 5 – Modern Activity in the area in the modern period was fairly minimal. It seems likely that the initial excavators of the room cleared down to the level of the threshold, and not much further. The bar counter was reached as there is some evidently modern consolidation mortar used to shore up the dolia support holes. Dolia were still apparently visible in 1875 at the time of Fiorelli’s writing. He stated that there were three dolia set into the ground, probably as a result of incomplete excavation to the level of the sunken floor. His plan, however, shows a U-shaped bar with additional dolia, of which this year’s investigations showed no evidence. The dolia seem also to have been spoliated or destroyed at a later date, as no trace of them was recovered. A small horde of imperial period coins was recovered in the vicinity of the southern most dolia hole, collected in a manner that suggests the activities of early excavators gathering them for consignment as a group, before absent-mindedly forgetting them. |

Figure 11. Stairs descending to the basement level at left, plastered wall and vault construction at right.

Figure 12. Probable early brick quoin at centre, knocked down to extend the wall.

Figure 13. Shuttering visible on underside of vault.

Figure 14. White plaster on basement wall.

Figure 15. Highly degraded cocciopesto floor with visible marble fragments inset.

Figure 16. Three dolium-support holes in the construction of the bar counter.

Figure 17. At the back of the room, the added wall floats over degraded cocciopesto, visible only in section.

Figure 18. Collapses through the floor of the room, exposing the basement level.

Figure 19. Stepped sequence of natural soils. |

Figure. 20. Early opus africanum property wall.

Figure 21. North-looking view of early fauces beyond brick extension walls.

Figure 22. Impluvium with multi-coloured stone mosaic.

Figure 23. Decorative stones in lower impluvium.

Figure 24. Floor in fauces and rhomboid pattern mosaic.

Figure 25. Cistern in southeastern corner of room.

Figure 26. Preserved original extent of primary opus signinum floor.

Figure 27. Extension walls with brick-banding and opus vittatum corners.

Figure 28. Sacellum, blocked threshold, and truncated sarno limestone wall.

Figure 29. Southern extent of drain |

Archaeological Area AA010

The original intentions regarding AA010 were to clean off the modern debris covering the opus signinum floor of the fauces and atrium at doorway 11 in insula VII 6 and to record the preserved remains through drawn plans, photographs, 3D survey, and 3D photogrammetry. Portions of the floor were still visible amidst the rubble and modern overburden, which had reached a height of approximately 50-60 cm in the north-eastern corner of the room. The initial excavation of the property had only summarily documented the features of the room and had not recorded it in detail. The clean of the area revealed a variably preserved opus signinum-lavapesta floor, with several additional phases, and a unique impluvium decorated with multi-coloured stones. Given the early, scant record of the property and the quality of the decoration in a property of unknown use/history, we decided to focus on an extensive program of recording in the atrium as well targeted excavation in those few areas where the flooring was not well preserved in order to better understand the developmental phases of the property. AA010 extended from the threshold of doorway 11 and filled the atrium of this property, approximately 7.50 metres wide by 10.30 metres long. Phase 1 – Natural Soils A yellow-brown soil was found at a relatively shallow depth, approximately 50-60 cm, in a rectangular hole left by a significant cut in the opus signinum floor. This same yellow soil was also discovered at a shallow depth in AA011. This yellow-brown soil appeared to be devoid of cultural material, but was not excavated in AA010 during the course of the 2014 season. Directly below this yellow-brown soil was a sandy, rich brown soil that was also devoid of cultural material and must constitute part of the natural soil sequence in this northern corner of insula VII 6 (Fig. 19). This rich brown soil was also not excavated in AA010. These natural soil deposits were uncovered directly below strata with intensive anthropogenic use. Specifically, both of these natural soil deposits were revealed by the removal of a thick, compact rubble deposit that was filled with building debris, such as mortar, unfinished plaster, fragments of floor, and small stones. Both natural soil deposits were also stepped, which resulted either from the natural formation of these soil deposits or by human intervention for the construction of the surrounding architecture. Though an adequate amount of these two deposits was not recovered so as to permit broader analysis, it is clear that these natural soils form the base later for the earliest human activity in this area. Phase 2 – Earliest Activities The earliest phase evident in AA010 is a north-south running opus africanum wall that forms the western terminus of the property (Fig. 20). This wall is composed of sarno stone that has been finished in large rectangular blocks as well as smaller, irregularly shaped pieces. The large rectangular blocks are set up in vertical and horizontal chains that have been filled in with the smaller, rubble sarno stones set in an earthen mortar. This opus africanum wall appears to run the entire western terminus of this property, though it is poorly preserved in height and a 60-70 cm section is absent. The eastern face of this wall was also plastered, though this coating is very poorly preserved and only visible in a few sections near the base of the wall. This early africanum wall was not excavated at greater depth, therefore its precise relationship to earlier phases of this property remain unknown. It currently believed that this wall formed one of the earliest property boundaries in Insula VII 6, which was later adapted and incorporated into a new property and a remodelled shop in the northern end of the insula. Further investigation of the extent of this wall will clarify the date of its construction, its original function, as well as the relationship of possible earlier architecture in this property. The investigation of this wall and these questions will likely form one of our research goals for the 2015 season. Phase 3 – Early Fauces, Impluvium Cistern, and Primary opus signinum/Lavapesta Floor Phase 3 is represented by the construction of the original fauces of the property and the articulation and decoration of the room as an atrium. The fauces walls were slightly more recessed from the street front than the AD 79 preserved walls and also did not extend as far south as the current preserved walls. These walls were built in opus incertumusing sarno stone, black lava, and cruma, all set into a distinctive pink mortar. The interior face of each wall was plastered, the remains of which are still visible at the base of each wall (Fig. 21). During the articulation of this property, an impluvium was constructed and decorated in the middle of the room, just south of the termination of the fauces. The primary build of the impluvium was constructed from sarno stone, brick, and tile that were mortared together in courses. This formed the supporting substructure of the impluvium, which was subsequently decorated with a multicoloured stone mosaic on its top and lower surfaces (Figs. 23, 24). The mosaic contained stones that were approximately 3-5 centimetres in length and 1.5-2.5 centimetres in width that were arranged in an irregular chequer-work pattern. Stones were white, black, red, green, and yellow in colour and were set into a opus signinum-like mortar atop the primary build of the impluvium. Some of these stones have been identified, namely Caserta limestone and Giallo Antico marble; however, the remaining stone types have yet to be classified. Another impluvium with this type of decoration is unknown among the Vesuvian cities; however, stones of similar colours and a similar sectile-like technique are known in the Casa del Fauno and the Casa di Torelli del Bronzo. A different opus signinum mortar was subsequently poured atop the sloping sides of the impluvium, forming a thick lip, though this action may have occurred at a slightly later date. The construction of a opus signinum-lavapesta floor, very fine and durable in quality, accompanied the construction and decoration of the impluvium. This floor contained small, vibrant red fragments of pottery, brick and tile as well a high concentration (50% of the total matrix) of very small black lava fragments. Both this floor surfaces and its grey mortar subfloor were approximately 15 cm thick (30 cm in total) and were built upon deep rubble levelling layers. The western half of this rubble layer was approximately 30-40 cm deep, though it sloped steeply and increased in depth to the south. These deposits were very compact in both material and soil. Fragments of red slip recovered from this deposit provide a TPQ of 15 BC for the construction of the floor. In contrast, the rubble layer in the eastern half of the atrium was comprised of very loose, sandy soil and very large fragments of building materials. It was excavated to a depth of nearly 80 cm before excavation ceased due to inaccessibility. In addition to the pottery and lava fragments, the floor was decorated with inset stones that are also found in the impluvium mosaic, small white and black tesserae, and a rhomboid band of white tesserae that spanned the width of the fauces (Fig. 24). Based upon its placement, this decorative band marked the termination of the original fauces. The surface also incorporated four large, rectangular marble fragments, (one now missing) at the front of the fauces near the threshold. Two of these marble plaques were a white marble, while one was quite clearly Cipollino. This opus signinum surface was poured directly against the fauces walls (and the plaster facing), the edges of the impluvium, as well as the eastern wall of the atrium, a sarno stone opus incertumwall with brick banding that runs north-south. This surface constituted the main floor until its destruction during the AD 79 eruption of Vesuvius. A cistern was also built contemporaneously with the construction of the impluvium and opus signinum floor, which formed the top cover of the cistern itself (Fig. 25). It was constructed in the south-eastern corner of the atrium and incorporated the southern edge and south-eastern corner of the impluvium. The top surface of this cistern was revealed as well as a quarter of the black lava stone that formed the cistern head. This cistern and the primary opus signinum floor ended at a black lava threshold and sarno stone and cruma opus incertumwall in the southern end of the atrium, which constituted the definition of and point of access for the rear rooms of this property and is also defined by a different opus signinum surface. Phase 4 – Truncation of Atrium, Remodelling of Northern End Phase 4 entailed significant remodelling of the northern end of the atrium and property. The fauces walls were embellished with brick end piers at their northern ends and were extended further to the south. These extension walls were built using sarno stone, set in opus incertum, as well as a high course of brick-banding and opus vittatum corners. This southern extension necessitated the truncation of a short span of the original opus signinum floor. This truncation is evident in the cut and surface void above the foundations of the back wall of the western shop at the front of the property, which were built directly against the truncated floor. This extension wall was built over a small, remaining rectangular portion of the floor at the northwest corner of the atrium and also breaks through the original property dividing opus africanum wall (Fig. 26). Both new rear walls were built against the pre-existing rubble levelling deposits, thought the cuts in the pre-existing opus signinum floor differ in width. Only the western wall was constructed upon proper foundations (Fig. 27). The extension of the fauces also provided the small addition of space to the shops/rooms at the northern end of the property. The top brick-banding course facilitated the construction of an upper story and a step/stairway was constructed against this wall in the western half of the atrium by cutting into the pre-existing floor and creating a mortar footing. This room also preserves one large beam hole that would have formed part of the supporting structure for an upper story. The rooms at the front of the property comprise two different types. The western shop was built with an entrance opening onto the street; the eastern room was closed to the street, but allowed access to the atrium through a doorway built in the new rear wall. Phase 5b – Remodel of Eastern Front Room Phase 5a involved a quick remodelling to the shops/rooms at the northern end of the property. A rectangular cut was punched into the recently extended western fauces wall in order to make a doorway and allow access into the western front room. Two large sarno stone blocks form the base of this doorway (and were a part of the original western fauces wall, as they still preserve traces of plaster on their eastern face). This action put the recently added upper story out of use, as it compromised the strength of the supporting wall, and would have perhaps interferred with the height of the new doorway. The surviving beam holes were blocked as the upper storey went out of use. Phase 5a – Remodel of Western Front Room Phase 5b involved the creation of access from the street front to the eastern front room of the property. This was effected by chipping through the brick façade of the shop in order to create a proper entrance to the room, thereafter likely used as a shop. Chips in the brick are only visible on the lower portion of these brick walls, as the upper courses have been conserved and replaced in the modern period. A black lava threshold was also inserted to define the entrance of the space. This action may have taken place simultaneously with Phase 5a, though there is no stratigraphic material to link these two changes. Phase 5c – Construction of Sacellum or Cooking Platform and Truncation of Rear Atrium Wall Phase 5c is defined by the construction of an arched structure, here identified as a sacellum or cooking platform, against the eastern wall of the atrium and the contemporaneous truncation of the rear wall of the atrium to re-establish access to the rear rooms of the property. The sacellum is an arched, opus incertumstructure that was constructed upon the primary opus signinum floor and abuts the eastern wall of the atrium (Fig. 28). Lava, tuff, Caserta limestone, sarno, cruma, brick, and tile composed the building materials. The upper surface of the sacellum, however, is poorly preserved. Its identification as a sacellum stems from the discovery of a white Carrara marble statue base that had either fallen or been pushed into the tile drain cap at the base of this arched structure. This base preserves a metal fixture for a sculpture, though no sculpture or sculptural fragments were found. This base and its accompanying statue could have formed a possible element of the sacellum and its decoration. The construction of this sacellum blocked the rear black lava threshold and thus would have interfered with access to the rear rooms of the property. As a result, the rear sarno stone and cruma wall was truncated to the ground level. This action drastically widened the doorway and reoriented access to the rear rooms of the property. This new doorway also mirrored the doorway that was constructed in the rear-wall extension of the eastern shop of the property. |

|

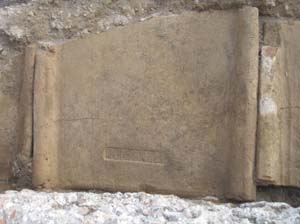

Phase 5d – Furniture Footing Phase 5d involved cutting a fairly regular rectangular hole into the primary opus signinum floor and subfloor against the extended fauces and shop wall and foundations. This action cut very clean, rounded, straight lines into the opus signinum surface and mortar matrix of the sub-floor and removed a section of these two features in order to insert a piece of furniture or other fitting. It is currently believed that this furniture item may have been a strongbox or and equally substantially sized item for storage. No material was uncovered in the course of the excavation of this hole that would provide additional clues as to its purpose. Phase 6 – Drain Construction and Realignment Phase 6 was characterized by the realignment and construction of a new drain in the property. The original drain and cistern overflow are believed to have run under the black lava threshold in the south-eastern corner of the room. At some point this drain ceased to function and necessitated the construction of a new drain. This new drain ran northwest from the black lava threshold in the southeast corner of AA010, along the eastern edge of the impluvium, and through the centre of the fauces. It exited below the lava threshold at the entrance to the property and through the sidewalk (see AA011). It was constructed by cutting two narrow, non-contiguous trenches into the primary opus signinum floor, one along the eastern edge of the impluvium and one extending northwest through the fauces from the northeast corner of the impluvium. The southern extent of this drain was partially exposed by the later collapse (probably of a nearby cistern), making the different components of the build of the drain visible (Fig. 29). The primary build is in opus incertumand incorporates sarno stone, lava, cruma, brick, tile, and small fragments of pottery and opus signinum. The drain was topped by large pan tiles, which were deliberately broken in half (as evident from the score marks on multiple tiles) and then fitted atop the parallel sides of the drain. These were mortared into place with a very strong and compact brown, earthen mortar. One of these tiles preserved a rectangular stamp with the name “Holconius;” the rectangular impression of another possible but illegible stamp was visible on another tile (Fig. 30). The tile with the best-preserved stamp was removed in order to better understand the interior build of the drain and remove a sample of fill of the drain. The interior of the drain is rectangular shape, measured approximately 20 cm wide and 20 cm, deep, and was lined with waterproof plaster that was a vibrant red in colour (Fig. 31). This red colour may be due to staining from iron elements. A small sample of the soil inside the drain was removed for soil and ecofactual analysis; very little cultural material was recovered from the deposit itself. This extent of the drain and the cuts made to construct and/or service it were then covered using a very different opus signinum, which contained very large fragments of pottery, lacked lava inclusions, and was generally poorer in quality (at least in its preservation). The northern extent of the drain differed slightly. The cuts for this section of the drain also produced a parallel trench, but one that was slightly more narrow. These cuts extended from the northeast corner of the impluvium, where a black lava drain cap was also inserted as part of the same action, and ran to the western edge of the threshold at the north end of the property’s fauces (Fig. 32). This was subsequently filled in using a opus signinum that differed from the primary opus signinum in the atrium; however, it also differed from the opus signinum used to cover the southern extent of the drain. The opus signinum over the northern extent of the drain incorporated very small, deep red fragments of pottery and was generally more compact and durable than the surface covering the southern extent. Given the preservation of this surface, excavation was not undertaken to reveal the drain in a second area in the property. A new drainage channel and pipe for the supply of this new drain accompanied these construction activities. It was cut into the opus signinum lip of the impluvium in the northeast channel and pipe corner and a ceramic pipe was inserted (Fig. 33). This channel and pipe were excavated solely to the point at which all modern material had been removed and the features were visible. The construction of a new drain in this property is believed to be one of the final phases, one that may have been necessitated by damage sustained during the earthquake of AD 62. Phase 7 – Eruption and Destruction This property, like the entirety of the city, was destroyed by the eruption of Vesuvius in AD 79 and buried under eruption debris. The atrium of this property, however, preserves evidence of damage sustained during the eruption. The cistern in the south-eastern corner of the room appears to have collapsed at this time. Extensive excavation of this cistern and its collapse was impossible due to the instability of the structure and the degree of modern contamination. Thus, the presence of eruptive material in the fill of the cistern could not be confirmed, but remains a strong likelihood. This particular structure and area of the atrium, however, remains an interesting point of investigation concerning the layout of the interior of the property. Phase 8 – Modern The area covered by AA010 was significantly impacted by modern intervention and events. Following the removal of the eruption debris, the area was inadequately recorded by its original excavators. Consequently, the decorative scheme and uniqueness of the impluvium remained unknown until its re-excavation this year. Areas of the property also appear to have been improperly restored during the Bourbon period, including the infilling of the doorway in one of the extension walls from Phase 4, which was originally open in antiquity. The area was bombed in 1943, with one impact site immediately to the west. The blast destroyed walls and other architecture in close proximity, including a portion of the opus africanum western property wall. Subsequently, the eastern and southern halves of AA010 became sites for dumping modern waste and debris, which piled up to heights that often exceeded 50 cm and intruded deeply into the collapse cistern, contaminating its contents. Finally, vegetation has caused an extensive amount of damage to the primary opus signinum floor and impluvium by uprooting and fragmenting the surfaces of these features to the point of near destruction |

Figure 30. Tile stamp with “Holconius.”

Figure 31. Uncapped and excavated interior of drain.

Figure 32. Northern extent of drain, lava drain cap, secondary opus signinum surface.

Figure 33. Cut in impluvium for new drainage channel and pipe.

Figure 34. Potential ritual deposit with black gloss, bone, and charcoal included. |

Figure 35. Highly charcoal-included deposit at left.

Figure 36. Yellow, redeposited natural soil and associated cuts and fills.

Figure 37. Drain running north down the fauces of doorway 11, and continuing across the sidewalk. |

Archaeological Area AA011

The 2014 season also included a brief excavation of a trench in the sidewalk in front of the fauces of doorway 11, investigating the association of the sidewalk with the house or inn investigated by AA010. Phase 1 –Ritual deposits The earliest activity uncovered in AA011 was that of a potential ritual foundation deposit, characterized by an incredibly high charcoal content. Indeed, the majority of the material was charcoal. Approximately half of a ribbed black gloss vessel was placed inverted over yet more charcoal in the vicinity of animal bones that seem to have been mortared to several fragments of sarno stone (Fig. 34). These objects were then also buried by a soil that also contained a high percentage of charcoal (Fig. 35). Perhaps this activity was related to the foundation of the house or the shifting of the limit of the frontage of this area. Further and more extensive investigation will be required to narrow down the potential causes of this activity. Phase 2 – Cuts and deposits Phase 2 saw the repeated cutting and filling of various linear pits for an as yet unknown purpose. Changes to to width of the sidewalk or the properties behind it may have been one of the reasons for these activities, especially since one of the deposits appeared to be a re-deposited natural soil with waterproof plaster included in it, that could easily derive from such activity. This deposit’s limit, a very linear vertical cut, suggested a possible sidewalk fill that no longer reached the kerbstones (Fig. 36). However, the potential for the widening of the sidewalk must remain only one possibility as there is no direct evidence that survives for the movement of the kerbstones to the north. Phase 3 – Drain and opus signinum walking surface The drain from Phase 6 of AA010 exited the fauces of doorway 11 and crossed the sidewalk to evacuate water into or under the street (Fig. 37). This drain was cut into the earlier deposits from phase 2. After being constructed it was capped and covered with a beaten earth that formed the foundation for a black lavapesta walking surface (Fig. 38). This drain was found to be very rich in finds, including several worked bone objects (hair pins, hinge), copper alloy coins, a small, highly worn marble statue base, rounded ceramic discs of unknown function, gaming pieces, and glass, possibly suggesting that much of this material may have been pushed down the drain by the eruption itself. Where and how the drain penetrated the kerbstones to evacuate its contents is unknown, as the kerbstones on the northern side of the trench had been very heavily disturbed by modern activity. Phase 4 – Modern activity The sidewalk has suffered a great deal of modern intervention, beginning in the mid-20th century. A WWII bomb clearly hit in the Via del Terme just to the west of AA011 destroying the sidewalk and knocking the kerbstones loose, including the western most of the four that comprise the north boundary of AA011. For this reason, it was not possible to recover the evacuation point of the drain onto the Via delle Terme. Additionally, with the construction of the modern Cafeteria of the Scavi, an iron water pipe was installed along the northern half of the sidewalk, cutting through the ancient deposits along the south half (Fig. 39). Re-filled with lapilli, the water pipe trench is likely to have been put in during the 1950s or 60s. Below this, an even earlier pipe, apparently in lead (but clearly of modern manufacture) was separated by a row of concrete tiles. The purpose of the earlier pipe is unclear. |

|

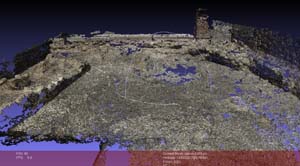

Finds Processing, Ecofacts, and Pottery Analysis Excavation in 2014 was paired with contemporaneous processing, analysis, recording, and study of all artefacts recovered from AA009, AA010, and AA011. This season witnessed the complete cleaning, documentation, and preparation of all materials recovered from excavation. As a result, there is no large backlog of material to be examined or recorded and study, citation, and digitization of this record can commence and continue through the autumn of 2014. Excavations recovered 19.16 kilograms of pottery during the 2014 field season, all of which has now been washed, accessioned, and prepared for sorting, analysis and illustration. In addition, material recovered during the 2013 field season was examined and recorded by Dott.ssa Victoria Keitel. All of the pottery from AA008 was weighed and sorted, and the diagnostic sherds were all analysed and illustrated. All of the pottery from AA007 was also weighed and sorted, and the majority of the diagnostic sherds have been analysed and drawn. Pottery recovered from the most important contexts in the 2014 excavations were examined to aid preliminary phasing and dating the site, such as the identification of red slip. Fine-ware fabrics were identified using a field microscope. Any remaining pottery from this year’s excavations has been washed, accessioned and recorded in preparation for processing and drawing in 2015. This season also saw the analysis and identification of coins from 2010-2014. Dott. Richard Hobbs of the British Museum has now processed and analysed all coins recovered by the Project to date. He has been able to identify the vast majority of the coins providing solid TPQ data for many of the stratigraphic units in our excavations. Finally, all soils from AA009, AA010, and AA011 have now been floated using a bucket-flotation method. As usual, light fractions have been reserved for study by environmental specialists and heavy fractions were sorted throughout the field season, recovering material smaller than the 0.5cm mesh employed in dry sieving. Finds included terrestrial and marine bones ranging from mouse to fish, shells, sea urchin, and charcoal, including numerous seeds. All remains were sorted and organised awaiting study by our environmental specialists in 2015. Sorting of heavy faction this season identified two deposits in particular that were very rich in mineralized seeds and appear to have derived from toilet refuse. 3D Topographic Survey and Structure from Motion (SfM) Data Capture The major focus of Total Station survey in 2014 was the use of the instrument to supplement traditional planning and 3D Structure from Motion (SfM) data capture in AA009, AA010, and AA011, in continuation of similar work undertaken in 2012-3. As a result, all features recovered throughout our excavations have been added to the wire-frame model of the Insula produced in previous years. In AA009, those features pertaining to the underground cellar that were excavated this year have been surveyed in anticipation of work necessary to plan further excavation of these rooms in 2015. In AA010, the extent of preserved lavapesta flooring in the atrium and fauces has been surveyed, along with the impluvium and the later drains. In all cases the bases of walls, which were not visible in 2006 when this area was first surveyed by the VCP, have been resurveyed in order to add them to the full wire-frame model. All surveyed areas were connected to previous models and are geo-referenced via the geodetic points placed by the SAP along the Via Consolare and Vicolo di Narcisso. As in previous seasons, a Leica TCR805power Total Station was used in combination with a Leica GMP111-0 Mini Prism to conduct the survey. All measurements were taken in either Reflectorless Standard or Infrared Fine mode. Every effort was made to maintain a fine level of accuracy (± 1cm) in order to produce a 3D model useful not only to this Project, but also for the Soprintendenza Archeologica di Pompei, and the wider community of Pompeian archaeological research. Excavation in AA009, AA010, and AA011 was carried out with complete recording of every excavated deposit in 3D at a centimetric level of accuracy. Each stratigraphic unit, feature, and pavement was recorded using Structure from Motion (SfM) technologies6 to extract millions of 3D points and colour information from an unordered series of photographs. After processing, these are meshed with Meshlab software designed specifically for cultural heritage projects by the University of Pisa, and developed with the support of 3D-CoForm Project. Following this stage, each mesh is coordinated into a 3D model of each trench, including all surfaces of each deposit, wall, feature, and pavement, permitting a complete reconstruction of the entire excavation and even the virtual ‘re-excavation’ of deposits recorded in 3D. Structure from motion calculations are performed on project computers employing free, open source software and without compromising the intellectual property of the SAP. Mesh results are coordinated within the wire-frame survey produced via Total Station survey, which provides the appropriate scaling and geo-referencing data for the production of a complete 3D model. For pavement surfaces, such as the preserved flooring and impluvium in AA011, this will permit the production of highly detailed scaled texture files of use for recording and in future examination of the surface, and for future 3D modelling and reconstruction of the area. |

Figure 38. Drain and final phase black lavapesta walking pavement.

Figure 39. Modern pipe cut for cafeteria waterpipe.

Figure 40. Statue base recovered atop drain in AA010 in 2014. |

Figure 41. Resulting AutoCAD dxf from 2014 survey showing AA009, AA010, and AA011.

Figure 42. 3D point cloud of AA010 produced with structure from motion (SFM) technology.

Figure 43. 3D point cloud of AA009 produced with structure from motion (SFM) technology.

Figure 44. Shop, Great Cistern and Steps to Cellar in AA009.

Figure 45. Drain running through AA010.

Figure 46. View of North end of Insula VII 6.

Figure 47. View from Insula VII 6. |

Conclusions and Current Interpretations

Overall, the excavations in AA009, AA010, and AA011 have provided a wealth of new data about the north-eastern corner of Insula VII 6 that not only helps to refine and solidify our understanding of the development of the block over time, but also provides significant and striking new insight into the nature of the block and its appearance at the time of the eruption itself. The new information we have uncovered has therefore served to reinforce and strengthen the narrative of urban development and change resulting from our previous seasons of research and excavation, while the discovery of unexcavated cellars and eruptive phase deposits that were either omitted or overlooked in the original excavations over 150 years ago hold the potential for providing and even greater window onto condition of the area in AD 79. At this time, it is therefore reasonable to present some of the major observations and possible implications of our results as they stand at the end of the 2014 field season. Great Cistern – A Pompeian Casseggiato? Our now deeper understanding of the final state of the buildings on the north-eastern corner of Insula VII 6 only serves to augment our previous observations regarding the creation of the Great Cistern and its impact upon the trajectory of urban development of Insula VII 6. It is now clear that the north-eastern corner of the block underwent a dramatic transformation, from a series of smaller shops or houses into a comprehensive and monumental complex that included a massive new cistern for the Forum Baths integrated with shops and apartment dwellings in a unified programme of urban intensification. These new facilities were excavated to considerable depth, most clearly witnessed in the Great Cistern itself, but also providing the shop at VII 6, 13-15 with an unusual vaulted double roomed cellar of significant scale, the precise purpose of which must be investigated in future years. Similar efforts to excavate to depth possibly also now present the best re-interpretation of the ‘cistern’ uncovered in our excavations of 2013 in VII 6, 16 (AA008). This suggests that the first stage in this process was the widespread removal of soil in multiple locations on the eastern side of the block, or perhaps that the original topography of the area was uneven. Certainly, it must be significant that similar subterranean rooms characterize the western side of the block in the Casa della Diana (VII 6, 3.4). The result of the construction of the Great cistern and its dependent structures, which reached at least three stories and now appears to have spread across the greater half of the properties on the eastern side of the block, presented a similar degree of social fusion between public infrastructure, commercial space, and private dwellings that may be observed in the insulae of Ostia. Dating evidence from our excavations makes it apparent that this change occurred at about the beginning of the reign of Tiberius, or maybe a little later, making this one of the earliest examples of this form of urban intensification. This new perspective on the north-eastern corner of Insula VII 6 casts the whole area of the Forum Baths in a new light as a sort of hyper-urban densely occupied downtown. The vaulting that was once present over the Vicolo delle Terme and remains of similar half vaults on the north face of the women’s part of the Forum Baths suggest the possibility that similar high-rises existed in these spaces and were possibly even connected. “L’impluvio quadrato, decorato intorno con una fascia di opus segmentatum”7 It is also clear that the creation of the Great Cistern and its associated apartment complex had significant impact upon the rest of the block as well, including the expansion of the Casa di Secundus Tyrannus Fortunatus (VII 6 28.19.20), which included space that was apparently liberated by the destruction of earlier properties.8 Similarly, the creation of the small but elegant house or inn at VII 6, 10.11.16 appears to have opportunistically filled in the space left by the larger municipal constructions on the east. Elements of the earlier properties, situated at an interestingly high elevation with respect to the surrounding area, seem to have been reused for different purposes. The prime example of this is the central impluvium, decorated with stone mosaic of a size, shape, and stone type that appears to date to the same period as the "Hellenstic" examples of the Casa del Fauno. That such an interpretation is possible is supported by the western wall in opus africanum and clay mortar, long identified by the VCP as a primary element in the layout of the block. Perhaps what later became the base of an impluvium was orignally a decorated room associated with this earlier construction. If this does represent an earlier floor reworked into an impluvium base, then it was clearly once quite a bit larger, since elements from the floor were also used to decorate the surrounding opus signinum. It is clear that the municipal work to the east helped to create interesting opportunities, not only for the takeover of space not used by the Great Cistern and its associated constructions, but also for the conquest of earlier elements of luxury. In fact, though the property at VII 6, 10.11.16 was identified by Fiorelli9 and Spano10 as a possible inn, our work suggests that the a house is more likely especially given that the final layout of space within the property clearly differed considerably from its original arrangement. Since it is certain that the flooring recovered in our excavations this year is roughly contemporary with the creation of the Great Cistern and its associated structures, all subsequent changes to the property must have taken place within a relatively restricted period of time. The addition of a tile-capped extra drain, the creation of an upper storey, and the subsequent modifications to this system, including the removal of at least one upper storey room, therefore suggest an extremely active period of urban transformation in the period from the early 1st c. AD to AD 79. The creation of the Great Cistern therefore appears to have had long lasting effects. Implications for the earlier Property Divisions? The primary and most important goal of this season was to examine the subsurface of the north-eastern corner of the Insula to discover evidence for the earliest property divisions and to complete our understanding of the original layout of Insula VII 6. The recovery of well-preserved flooring in VII 6, 10.11.16, and unexcavated final phase cellars in VII 6, 13-15 interfered partially with this goal. However, sufficient material was recovered to reveal that the initial property divisions in this area conform largely with the system already discussed in our previous publications and reports, with only minor modifications. It is now clear that earlier structures were indeed present in these areas. In shop VII 6, 13-15, the earlier structure appears to have opened to the east, a fact that perhaps helps to associate this structure with the row of shops that was clearly in place on the southern side of the Great Cistern. Certainly elements of a facade in tufo di Nocera were reused in the construction of the three storey apartment complex that in all probability, derive from this very structure. This suggests that at an earlier stage the Vico delle Terme was a more important focus determining shop facing than the Via delle Terme. If the impluvium recovered to the west of this does indeed testify to an earlier floor surface, then it will be necessary to search for evidence for an earlier house or elite structure in this area. The hypothetical property divisions that the VCP has calculated in our previous work do permit the reconstruction of a house in this area, and it will be the work of the following months to search for further evidence for such an idea. Overall, the results of the 2014 field season have served to strengthen, support, and build upon the conclusions of our previous research. Much of the developmental history of the block has now been securely sequenced and is becoming well-understood. Nevertheless, there remain important questions to answer, especially in those areas of the insula where material from the eruption remains to be excavated. We will seek permission to excavate in these areas in 2015, as well as continuing our investigations and documentation of the urban development and chronology of Insula VII 6, the area of the Villa delle Colonne a mosaico and the Via Consolare. As always, we remain deeply indebted to the Soprintendenza Archeologica di Pompei, the Ministero per i Beni e le Attività Culturali, Soprintendente Prof. Osanna, Direttore dott.ssa Stefani, and Direttore dott. De Carolis, and extend our warmest thanks for their kind and continued support and encouragement in our research activities. Our work could not have been done without their aid. We owe much to the kind collaboration of Assistente Sabini in particular for sharing his profound knowledge of the city, and in particular in his help in covering the atrium and impluvium in AA010 with materials appropriate to help with their future conservation. Finally, we wish to thank our great friends at Bar Sgambati and Camping Zeus for their ongoing generosity and unending friendship toward the Via Consolare Project since its inception. |

|

|

||||||||

|

Website Content © Copyright Via Consolare Project 2018

| ||||||||